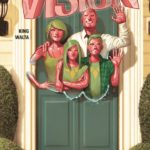

It’s the quintessential American Dream: a respectable government job and a house in the DC suburbs. The picture wouldn’t be complete without a beautiful wife and two happy children, or at least that’s what the Vision thinks. So he went to a lot of trouble and made them.

Nominated for a Hugo Award this year, Tom King’s Little Worse Than A Man (with illustrations by Gabriel Walta) shows what happens when a non-human hero is determined to live a human life. It’s a story that starts out light and then gets dark surprisingly fast.

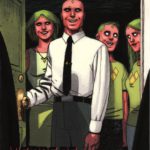

Don’t expect a lot of hi-jinks and cute misunderstandings with the Visions trying to hide their identity. Everyone in town already knows about the famous Avenger (he has saved the world multiple times, after all), so they’re aware that the new neighbors are actually artificial super-people. Everyone is certainly not OKAY with that, but they’re definitely aware.

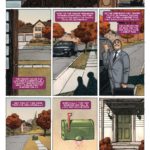

A major theme of this book is Keeping Up Appearances, so the first chapter plays up a little of the humor of everyone trying to act like all of this is normal. The neighborhood welcoming committee stops by, and Vision introduces his normal wife, son, and daughter (all three of whom are super-powered and can fly and morph through walls) and shows off his very normal house (filled with impossible artifacts from other planets), and thanks them politely for the tray of cookies they brought (which the Visions can’t eat, since they recharge with sunlight). Thank you very much for stopping by. Nothing. To see. Here.

After everything the Vision has gone through I can understand why he would want to have a peaceful family life. I just wasn’t sure why he particularly wanted this life. Why would he choose this almost 1950’s type of domesticity – in a place where he would certainly stand out as an alien – as the idea of a perfect life? But then, why do any of us chase the things we chase when we’re trying to find happiness? Maybe we’re deliberately following a template of family life that we’ve gotten from society. Or maybe all we have is a vague idea of what our lives need to be.

It’s even more nebulous for the Vision since he’s the first in his race; there’s no rules, no guidelines for what his life is supposed to be. With a million different worlds to choose from, why shouldn’t he live in the DC suburbs?

Sadly, the answer is because living here means he’ll be surrounded by defenseless civilians when things go horribly wrong.

The story lays on the foreshadowing pretty heavily, but we don’t have a lot of time to wait before the disasters start. Some of it is due to the Vision’s history, and the very dangerous enemies he’s made. Most of it though is a lot more insidious, and it has to do with fear. We’re all dealing with a lot of fear lately, and what King’s story forces us to examine is that for the person who’s afraid of other races or religions, and the person who’s afraid of being the target of racists, the emotion they’re experiencing is exactly the same. Sure, some fear is justified and some isn’t, but how do you tell someone who’s convinced that their family is in danger to just stop being afraid?

And are you prepared to become exactly what everyone is afraid of in order to defend your family?

The Visions are a sometimes touching and sometimes disturbing combination of alien and all-too-human. At one point we see the Vision’s daughter Viv (who is, don’t forget, a synthetic human with a computer for a brain) take a memory fragment of a conversation with a male classmate and turn it into a loop so she can quietly replay it over and over. Vision’s wife Virginia starts becoming more and more emotional as a crisis builds, but that emotion can show by repeating one word a dozen times before punching through a table.

And in one of my favorite scenes, the Vision finds himself running through the thirty-seven times he’s saved the world, mentally replaying each disaster (with Gabriel Walt’s sometimes dreamlike artwork) as he tries to justify bullying a high-school principal into not expelling his son, and then all the lies he’s having to tell to keep his family safe.

Lies trigger more lies, and the damage gets worse, fast. King and Walta show you just enough to give the sense of things getting out of control; at one point you get a chilling hint of what it looks like when the Vision loses his temper, and you don’t actually see it happen. The end of the book circles back to the beginning, and you know for a fact that things are going to get very very bad, but you won’t know exactly how.

I’m not sure if this story will actually win the Hugo this year (I think Saga will walk away with the award, but I’m kind of biased), but I can see why it was nominated, and it most definitely is worth a read.