…It isn’t the failure to communicate that fascinates me; it’s the implication that these ETIs appear to have no interest in communication at all. And we humans, vain, egotistical creatures that we are, can’t help but take that a little personally…

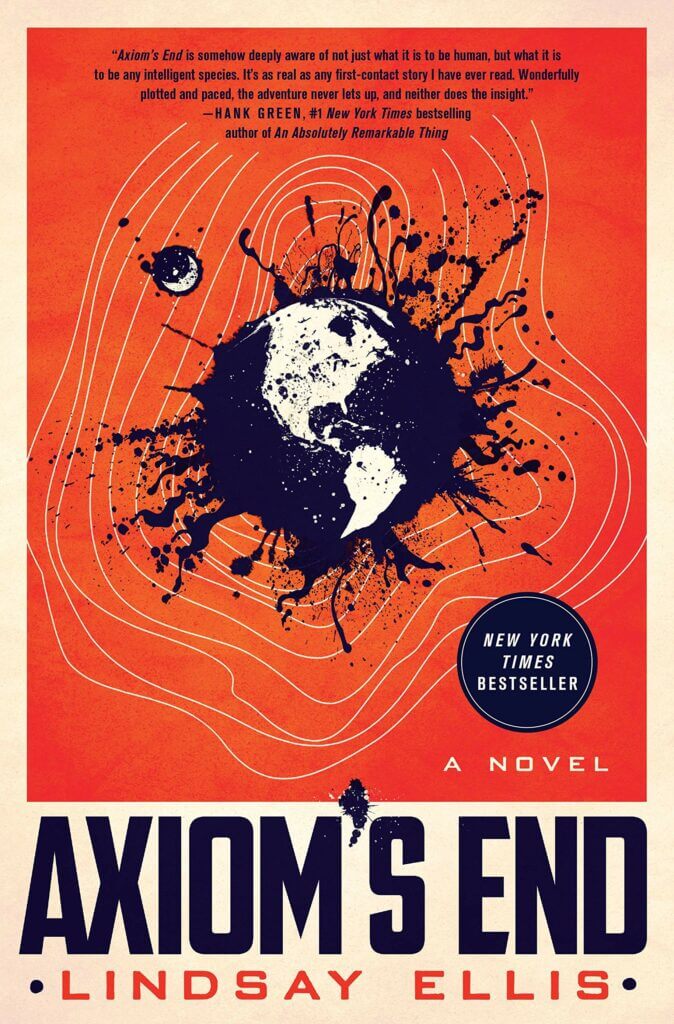

I’ve still got a few more weeks to add to my list of possible “Best of 2020” books, and with the constant news cycle of powerful government organizations trying to accomplish (gestures vaguely) something, this seems like a perfect time to review Axiom’s End by Lindsay Ellis (you remember Lindsay? Nominated for a Hugo for her Youtube trilogy The Hobbit Duology – a fantastic examination of just what the hell was going on with that series – which you really should watch.)

Ellis’s debut novel begins in 2007 with “The Fremda Memo”, a partially-redacted document that makes tantalizing references to forty years of attempts to communicate with “them”. Coincidentally (maybe?), the release happened right around the time an unidentified object fell from the sky into the hills of California: the Ampersand Event.

Fast forward to Cora, who’s spent the last month trying to avoid the relentless attention that comes with being the daughter of Nils Ortega, the fugitive journalist who released the Fremda Memo to the world. Any progress Cora has made in becoming forgotten is destroyed when a second object blows out the windows in the office building where she works, and then crashes close to where the Ampersand Event took place. Suddenly she’s the focus of both shadowy government agents and a strange alien force that doesn’t have a problem with kidnapping humans and injecting control devices into their brains.

I started out thinking that I couldn’t sympathize with Cora since she seemed to be determined to let her life stagnate; dropped out of college, dead-end job, using money set aside for bills to buy concert tickets so she could think about something else. Anything else. But it becomes clear that her father really has made a mess of her life. It’s tainted her relationship with her family members, taken away her privacy, and legions of fans have driven her off social media for even daring to suggest that she wants nothing to do with her famous but absent father. Who wouldn’t be a little glum after that?

Getting kidnapped by an alien life form and mind-controlled into walking into a government building makes her already complicated life quite a bit worse.

It had an oblong head like a dragon, if the dragon had no jaw and no nose, and even had a sort of crest that jutted out from the back of its head like a feather headdress. But it was the eyes that were most striking, the only part of it that wasn’t some shade of that iridescent white silver, big almond-shaped things situated on the sides of its head like a wasp, amber colored and seeming to glow as if there were a dim, internal light illuminating a gemstone, and those eyes were focused on her.

In anyone else’s hands a scene of an alien with no understanding of modern life or human rules for conversation trying to puppet a human into a high-security building might come across as funny, like a stack of cartoon animals wearing a trenchcoat. But here it’s deadly serious, because the alien controlling Cora is desperate. Desperate enough to use humans as blunt instruments to try to get what it wants.

When something happens that forces the alien to see Cora, really see her as a person, Cora has to decide whether to give her loyalty to a human government that’s possibly been damaging the brains of witnesses to wipe the memory of First Contact, or to work as an interpreter for an alien who sees humans as at best animals (and at worst terrifying meat-eating savages).

Cora chooses the alien – who allows her to call him Ampersand – because of course she does. Human or not, the government has spirited away her family and threatened her at every turn, not just to protect the Earth but to make sure American citizens never find out what’s been going on since 1971. Ampersand’s need to find the members of his race that have been held prisoner for forty years is at least marginally more understandable.

But still, only marginally. There are complicated things going on here. Everyone seems to have something to hide: Ampersand, the agents shadowing Cora, Cora’s own family. A simple search-and-rescue ends up being quite a bit more than that, and every time it looked like we have a clear picture of what’s going on, a new layer would be added and suddenly everything is seen in a completely different light. Even a simple act of translating Ampersand’s thoughts into instructions for other humans is complicated because Ampersand doesn’t know how to not be curt and demanding, he doesn’t realize when some of the things he says are really, really upsetting, and he has no problem speaking truth to power, even when that’s a really bad idea.

The secretary was trying to keep his gaze on Ampersand, not Cora. “Here in America, we consider ourselves equal. We stand on equal ground.”

“Categorically untrue.”

“He says he feels that’s dishonest,” said Cora flatly.

The story follow some First Contact tropes, but also draws a lot of parallels with how humanity has acted when meeting another civilization. It also asks some interesting questions about how we justify keeping secrets, or taking horrible actions when it’s for the good of society/civilization/our race/my family/insert your own tribal designation here. It even tackles the idea of anthropomorphism, where we assign human emotions and motivations to something that is not and never will be close to being human. Or the opposite, where we very quickly assign something or someone as “other” the moment it becomes inconvenient to think of them as part of the “right” group.

The discussion of these high-minded ideals never bog things down; you can really feel Ellis’s experience with film criticism in how she paces out the story. Block of exposition move along faster when there’s an underlying current of “my family is in danger, I don’t know how much of what this being who implanted a translation device in my brain says can be trusted and, oh yeah, the Earth is possibly in danger of being destroyed.” There are panicky, terrifying moments when a twenty-something college dropout has to deal with a technologically advanced race by either making a run for it – on foot – or try to beat it to death by hand. And there are also quiet moments, some of which I would really love to see on the big screen, like Cora and Ampersand under the Milky Way in the middle of the desert.

Best of all – and this is very much like catnip to me – is the growing relationship between Cora and Ampersand, when two beings who are about as different as you can be and still be sentient, who don’t even have the same concepts for gender and emotion and comfort, somehow manage to connect with each other, in ways that are beautiful and sometimes funny and real. The story is much more than a buddy adventure, and edges very close to an interstellar romance, with all of the heartbreak and uncertainty that comes with it.

By the ending of the book there’s a lot left to learn, both about the alien race that poses such a threat to Earth, and the human family member who seems to be acting as if he’s from a different planet from the family he claims he cares about. Plus, once we find out what the books title refers to, we can see that the two races discovering each other is only the start of huge changes for them all.