We won’t get another installment in Tamsyn Muir’s Locked Tomb Trilogy until 2022, so let’s take a look at her novella from last November, a fairy tale that’s as different from her Gothic space saga as you can get, while still being very very dark.

Floralinda is a lonely princess in a tower, waiting to be rescued by a prince. The witch who imprisoned her made sure she was equipped with a magical supply of oranges, milk, and two types of bread, and then placed a different kind of monster in each of the thirty-nine flights below her. The prince who battles through all of the monsters will win a golden sword and Floralinda’s hand in marriage.

Simple, right? The problem is that it’s been weeks, and no prince has survived past the first monster, much less the other thirty-eight. And the tower is really only a spring/summer type of home and winter is coming.

And Floralinda has come to hate the taste of oranges.

It is dreadful to think that a prince has been crunched up by a dragon all in the name of rescuing you; but when fully twenty-four princes are crunched up by a dragon while trying to rescue you, it s another thing altogether.

I don’t know if Rapunzel started the tradition of the princess-in-the-tower, or if she’s just the most famous example, but it’s pretty clear that Muir has put a lot of thought into what the actual situation would be for the person trapped like that. Sure, people throw the word “lonely” around, but think about just how bad that would be, cut off from everyone, alternately terrified and bored, unable to warn off the hapless princes after the first dozen or so are eaten, or to summon any more when the princes eventually stop coming.

It’s made clear from the start that the witch has simply set everything in motion with no intention of coming back until the princess is rescued (or any concern that a rescue might never happen). The discovery of the diary of the previous princess makes Floralinda realize that if she doesn’t want to spend the rest of her life in one room with the same four things to eat every single day (or throw herself from the window, also an option), she’s going to have to make her own way through all the monsters on every flight and out the front door.

What she finds on floor thirty-nine almost kills her. The appearance of a wounded fairy in her bedroom immediately afterward is surprisingly unhelpful.

“Those are goblin bites on your hands, aren’t they? They’re quite infected. Goblins are filthy. You’ll be dead in a week.”

At Floralinda’s new bout of tears, the fairy said a bit diffidently, “Cheer up, you might die earlier.”

The tone of this novella is almost sing-song, hilarious at times and with a storybook pacing, but this is not a story for children. You can forget about getting to defeat any of the monsters with a magical weapon or by solving a riddle; Floralinda manages to survive the first few flights by sheer accident, and part of that survival comes with having to boil her hands three times a day to kill the infection that’s turning her hands into a pus-filled mess.

Her new fairy companion Cobweb is bad-tempered, verbally abusive, completely lacking in empathy, and is only persuaded into helping because she (arbitrary gender, mostly assigned by Floralinda) is also way too proud of her own cleverness. The cleverness is what Floralinda desperately needs, because she has only orange peels and curtain rods to get past a towerfull of monsters.

And I do mean an entire tower, because the chapters count off every floor and every monster. Every. One. Sometimes we see an entire battle in all it’s horribleness, sometimes we only get the briefest mention of what was on a floor, enough for us to say “Hang on, how did they….” before it’s off to the next monster. It’s epic and upsetting, as Cobweb makes Floralinda cannibalize each corpse for…supplies, and Muir shows us every step of that gruesome process. The fact that Floralinda gets very lucky several times does not at all mean that any of it is easy.

Floralinda starts off as the standard princess: sheltered, a little silly, kind-hearted in a remote, saintly sort of way, and pretty much terrified of everything (fortunately it’s the kind of terrified that means she panics and flails wildly rather than doing the dignified princess thing of freezing and going pale). She doesn’t stay that way though. In addition to taking fairy tale tropes and gutting them for parts, the author’s overwhelming message here is that you can be nice, or you can be whatever you need to in order to survive, but you can’t be both. Ruthlessness mixed with cruelty is the order of the day, in ways that were sometimes shocking and made me wonder if I really should be laughing or not.

This is not a happy story, is what I’m saying. It’s not going to make you feel empowered, or leave you with much faith in human nature. I enjoyed the heck out of it. I loved all the minutia, the weapons being made by a fairy who’s gotten a taste for experimentation and fire, the witch’s motivations, the biological imperative of princes, and the transformation of the princess into someone who eats songbirds and does things that startles even her jaded fairy companion. I bought this one on Friday and ate it in two big bites, wishing I could have a few bites more after the ending, one which definitely implies that even the oddest happily-ever-after doesn’t mean that the story stops.

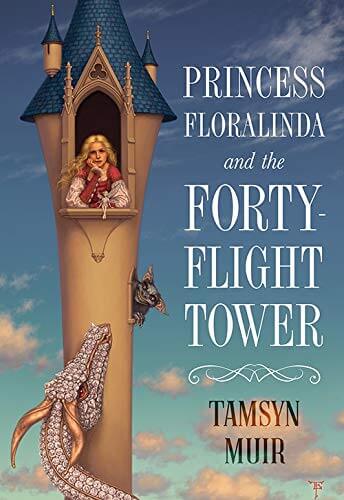

The gorgeous cover illustration is by Tristan Elwell.