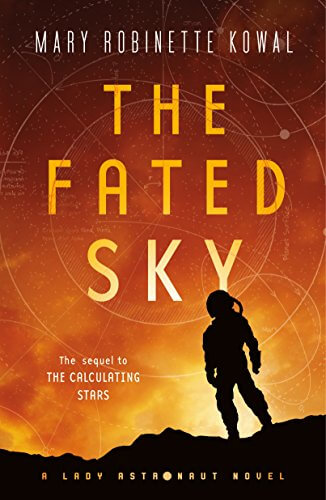

The third book in Mary Robinette Kowal’s A Lady Astronaut trilogy is up for a Hugo award this year and I…still hadn’t read Book 2, The Fated Sky. Time to get on that.

It’s been nine years since a meteorite wiped out most of the Eastern US and destroyed the Earth’s climate. In that time humanity has not only managed to land on the moon, they’ve established a colony there and are working on the next big project: Mars.

The work Elma York did in Book 1 and her role as the Lady Astronaut earned her a place on the Moon. She now spends her time shuttling back and forth between the colony, and her life on an Earth that’s quickly disintegrating, climate-wise, politically, and racially.

Sure, she would like to be part of the International Aerospace Coalition’s mission to Mars. But there are many astronauts who have already been training for months to go, and the trip would keep her away from Earth (and more importantly her husband) for three years. So it’s probably for the best that it isn’t an option.

Funny how quickly things change…

“People like you. They trust you. So…for the sake of the space program, I want to ask you to be the face of the IAC, and, specifically, to join the First Mars Expedition.”

Kowal has done a deep, deep dive into the technology available in the 1950’s, and how it might have changed if, say, the entire human race suddenly had a reason to flee the Earth and live on another planet.

There’s no hand-waving away problems here, no sci-fi magic like artificial gravity or transporters, no strolling from low-G to Earth-normal gravity and back again in a day. Acclimatizing back to gravity takes at least week, and traveling from one moving spaceship to another takes at least a half hour (with a 14-step process to open and close the doors). And you can count on the author to include as much of the math as possible and all of the fascinating little details about life on a spaceship. There’s real-life tech that would have actually been used in the 1960’s, like having to navigate with a sextant and most of the mathematical calculations being done by hand. There are fun facts like how you can cook in space, but all the herbs and spices are kept in oil because the last thing you want is little crumbs of pepper or dried thyme floating into the instruments. And then there’s the not so fun facts, like what an e-coli outbreak looks like in zero-g, and one option for disposing of a body when en route to another planet.

(Good God, “the bag”. I can’t remember another instance where two words have become so horrifying in a story. It’s apparently something that’s really and truly being designed for the space program, and the author does a masterful job of illustrating the gap between what scientists have decided is the most “efficient” method, and what the reality is for the people who actually have to watch it happening.)

The relationships and emotions of all of the characters are a lot more complicated than your usual space opera as well. Elma has been able to overcome a lot her crushing anxiety problems, but she still feels like she has to apologize for wanting to be good at something, especially since a lot of times she’s valued more as the pretty lady who can drum up interest in the space program, instead of her abilities as a computer. She also has a lot of guilt for taking up a very risky job and leaving Earth and her husband behind for three years. Not to mention the fact that if she wants to have her career and a life on a planet that isn’t Earth, then she pretty much has to say goodbye to any ideas about having children. It’s fortunate that Nathanial still gets the award for Most Supportive Spouse In A 1960’s Setting.

“I don’t want you stuck on Earth, wishing you were in the stars. That’s no sort of marriage.”

Oh, and Elma’s colleague Stetson Parker is still a complete ass. He seems to respect the abilities of the other women in the program more than he did in Book 1, but that doesn’t stop him from the constant stream of cutting remarks and “just a joke” comments. It really does feel like an abusive relationship when Elma has to spend so much energy trying to figure out what she can do to make him be charming instead of angry.

It’s part of what makes him so frustrating, because he can clearly read people well enough to know exactly which buttons to push to get what he wants. And sometimes what he wants is to be cruel.

By far one of the biggest problems the characters have to deal with is the problems of prejudice. These books are set firmly in the time of Martin Luther King Jr., the marches for equality, and Apartheid. If you thought the pending destruction of Earth would make everyone shift their attitudes, well, you’d be wrong. Only a few people say the quiet parts out loud (including a South African astronaut who really needs to learn the benefit of shutting the hell up). Mostly it’s the constant background radiation of “you’re more suited for these tasks (cleaning) than those (science)”, or “complaining about your treatment means you’re not a team player, and possibly a danger to the mission” and definitely “a pretty, white woman who can make Congress cough up money for the IAC is more valuable than the non-white female scientist who’s already been training for months.”

(If there’s one part of the book I didn’t enjoy, it was the relentless situation of Elma Being Wrong and Having To Apologize. I can’t really complain since it’s done very effectively and it’s an essential part of the story. Every instance demonstrates how being an ally is a delicate business, since charging in and trying to “fix” things from a position of privilege and ignorance is usually guaranteed to make things worse. But still, uncomfortable.)

Watching all of this go down makes the reader face how petty a lot of these attitudes are. It’s expecting the status quo to stay in place when entire races know know that it means it’s an actual option to be left behind on a dying Earthy. It’s putting an entire spaceship in danger because the more qualified person isn’t seen as such because they aren’t white. And in at least one case it’s turning down medical treatment because being sick and dying is somehow better than letting the “wrong” person touch you. (God, DeBeer, I can’t say this enough, shut the hell up.)

It’s a situation that’s extremely timely, applicable both to current day issues and a historical reality that really grounds the sci-fi elements. In one series you can have appearances by Walter Cronkite, Gus Grissom (piloting the Moon shuttle instead of dying in a pre-launch test), and Martin Luther King Jr. receiving a Nobel Peace Prize two years early, and Gene Roddenberry basing a character on his “new TV show” on one of the main characters. And you also have things like the miniature park of dandelions and prickly pears on the Moon, impromptu Flash Gordon radio plays, tastefully written sexy good-times in zero-G, some nail-biting peril, and tragedy that shows just how human everyone actually is.

This series started in the real, carefully-researched history, and by Book 2 it’s still in a believable 1960’s setting, but diverged enough to have some fascinating situations and settings. It kind of surprises me that Book 2 wasn’t nominated for a Hugo the way Books 1 and 3 were, and it makes me really look forward to seeing just how much things are going to change by Book 3.