I don’t blame them. I’m not angry. Everyone uses my name for a swear word but it’s so completely fine. They don’t know I’m beloved. But I know, and that’s plenty.

The Past is Red, Catherynne Valente’s sequel to her short story The Future is Blue, is scheduled to be released next month on July 20! This new novella continues the story of Tetley Abednego, the most beloved person in Garbagetown, which nobody but her knows since she’s hated by everyone on the entire floating island. By law.

I was able to get an advance reader copy of this novella, and I was planning on waiting a little longer to read it so the review would fall closer to the release date. Buuuuut…the first part of the book is the original short story, so I thought I would just reread that for fun. And then I took a quick look at the start of the new story, just to see if Tetley’s adventure begins where the last story left off.

And that was it, finished the whole thing in less than a day. Practically in one sitting.

You’ll definitely need to read The Future Is Blue before starting the new novella (I mean, The Past Is Red mentions what happens, but you need to read it anyway because it’s really good). To summarize, Garbagetown is the floating island where most of what’s left of humanity retreated to when the seas rose and the Earth drowned. Everything that was dumped in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch has been carefully sorted into the different types of trash, making separate neighborhoods in a floating continent that can take several weeks to walk across. Tetley sees Garbagetown as the most magical place in the world, a place where you can find anything you want in what was thrown away by Fuckwit Civilization (that would be us): food and shelter, but also treasure and adventure and even true love.

Then Tetley did a very bad thing and now everyone hates her.

Never mind that what Tetley did was save Garbagetown from being condemned to drift without power, in the dark, forever. It doesn’t matter; her fellow citizens were determined to throw away their future by chasing after a wild impossible something. And if there’s one thing no one will forgive, it’s taking away their hope.

“…the kind of hope I have isn’t just greed going by its maiden name. The kind of hope I have doesn’t begin and end with demanding everything go back to the way it was when it can’t, it can’t ever, that’s not how time works, and it’s not how oceans work, either.”

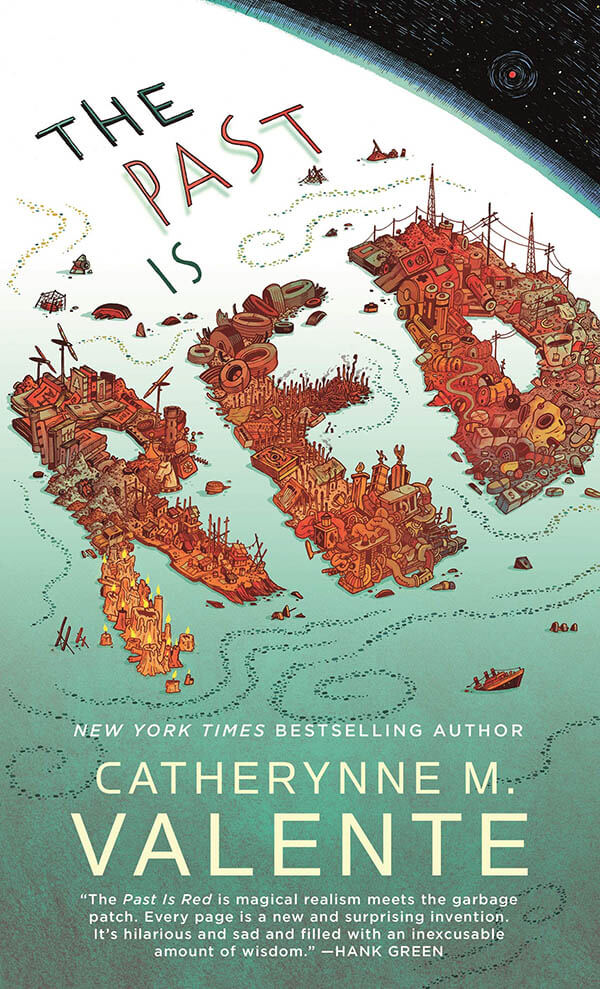

I’m not sure I can fully explain exactly how fantastical the setting of Garbagetown is. The intricate cover art by John Hendrix hints at a little of it. When I say that the garbage has been sorted into different neighborhoods, I don’t just mean one section for metal, one section for wood, etc. I mean each type of garbage. Furniture. Musical Instruments. Printer cartridges. Jumbotrons. Every few pages there’s more detail about how people live in each neighborhood, how they build their houses, what they name the boroughs: Penhege, Lost Post Gulch, Matchbox Forest, Mount VHS. Tetley wanders into a grotto of the cheapest, most garish gold you can imagine and it’s glorious, almost as spectacular as the city of thrown-away pharmaceuticals.

When the sun comes up or goes down, it turns Pill Hill into a wilderness of fire.

The story isn’t all whimsy and the world’s greatest Scavenger game though. Tetley’s punishment for saving Garbagetown is that everyone on the island is allowed to do anything they want to her – short of killing her, although accidents could happen – and she has to thank them for it. We’re seeing things from Tetley’s point of view years later, so we know she’s survived this. Tetley is resilient like you wouldn’t believe, she’s determined to greet every day with a sense of wonder and cheer, and at no point does she regret what she did or wish she’d done anything else.

And yet…

It’s a lonely business, being the most abused person in a city that’s built on the wreckage of the civilization that destroyed the world. She has an aching need to be loved again, something she readily admits is probably not ever going to happen. And what she’s finding out is that all the people in Garbagetown that hate her (ie: everyone) would give anything to have a little of what the Fuckwits had. Imagine having the energy to care about things like 2nd Place trophies and Daylight Savings Time, or exercising simply because you ate more than you needed. One of the most magical things that one person can think of is the idea of throwing something away.

I just want things to be easy like they used to be. I wanna be whoever I was going to be. I want to use up a whole toothpaste tube and throw it away with three-quarters of it left in the bottom because I just buy more tomorrow. I want to put my clocks forward in the spring and complain about it. I want to have to watch what I eat because it’s so easy to get fat. I want to go where everyone knows my name…”

And all of this is told in Valente’s lyrical prose. Tetley’s inner narrative and everyone’s dialogue is wrapped up in old TV show lyrics and advertising slogans and Valente’s startling ways of digging down into human nature itself, and it’s like someone combed through a trash heap for all of the prettiest bits and put them together into a masterpiece of poetry.

Being alive is like being a very bad time traveler. One second per second, and yet somehow you still get where you’re going too late, or too early, and the planet isn’t where it should be because you forgot to calculate for that even though it was extremely important and you left notes by the door to remind yourself, and the butterfly you stepped on when you were eight became a hurricane of everything you ever lost in your forties, and whatever wisdom you tried to pack with you has always gotten lost in transit, arriving, covered in festive stickers, a hundred years after you died.

Parts of this novella are just elegantly painful. Most of the story that Tetley tells actually happened. But some of it didn’t. And that hurts every time. The worst impulses of the characters here are also our worst impulses: to find someone to blame, to ignore the needs of others as long as our own needs are met, to talk about being free while looking for anyone to tell us what to do (our families, our church, our government, the shouty angry person on the radio or the Live-Laugh-Love influencer), and to keep on doing exactly what we’re doing even though we’re killing the planet one single-use plastic packaging at a time.

And yet it’s also stunningly beautiful, because even with all of the dark things going on Tetley (and by extension the readers) have reasons to be happy and reasons to be extremely depressed and sad and worried about the future, and a lot of times both the happy and sad ones are the exact same reasons.

Loss of love is made possible by having that love in the first place. Everyone hates the Fuckwits (and I can’t stress this enough, that means all of us) while treasuring the things they left behind and picturing a heaven where they could have everything we have right now. Tetley discovers a terrible secret that means she once again has to decide whether or not to save a world that will never thank her for it, but before that she navigates the worst heartbreak and having her dearest hopes answered, ending the story with new friends that I promise aren’t anything like what you’re expecting.