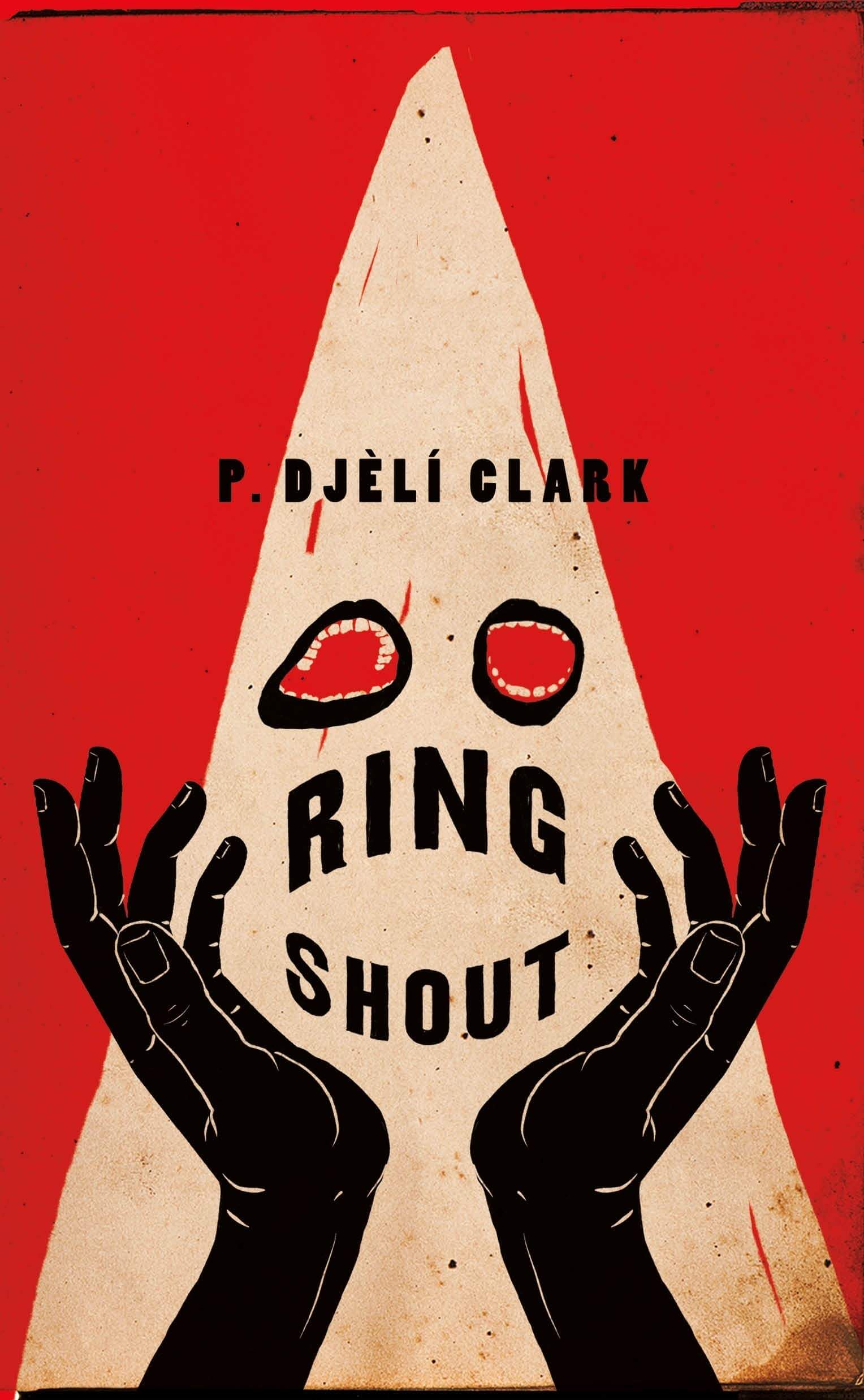

We’ve reviewed a few of P. Djèlí Clark’s novellas and short-stories in the past, all of them nominated for Hugo awards and most featuring actual history that’s been nudged into an alternate universe by the appearance of magic. Clark’s latest nominated novella is no exception, taking place in 1920’s Georgia.

Being smack in the middle of Jim Crow era in the South was dangerous enough for anyone not white, but in Clark’s lushly-described setting it’s gotten even worse, since the release of a certain movie in 1915 also released actual demons into the ranks of the Ku Klux Klan.

Stories say they read from a conjuring book inked in blood on human skin. Can’t vouch for that. But it was them that called up the monsters we call Ku Kluxes. And it all started with this damned movie.

If you’re wondering, this is not a story where the horrible acts in human history are explained away by saying that poor innocent humans were infected from something from another dimension. This is a real 1922 in the South, with the usual “Whites Only” signs, and Klan parades through the center of town, and the shadow of slavery is still hanging over people, both the ones who grew up hearing stories from the people who lived it, and the ones who wonder why things can’t go back to the time when everyone knew their place.

It’s just that in this version of history, the rage and poisonous nationalism capitalized on by the film The Birth of a Nation was used to call up demons in a ceremony performed by people who understood the power of hate but didn’t realize how dangerous it would be to let it loose. To everyone else these demons look like regular Klan members (maybe creepier, with a habit of gulping down water and being a little too interested in dead dogs), but to the story’s rag-tag group of monster hunters, they look like something quite different.

Arms of thick bone and muscle jut from its shoulders, stretching to the ground. But it’s the head that stands out – long and curved to end in a sharp bony point.

This is a Ku Klux. A real Ku Klux. Every bit of the thing is a pale bone white, down to claws like carved blades of ivory. The only part not white are the eyes.

The monster-hunters and their allies have been holding their own against the demonic Ku Kluxes for a few years, but they’re starting to hear rumors of another ritual at Georgia’s Stone Mountain, something that will use the re-release of D.W. Griffth’s film to bring another horror into the world.

So it’s lucky that the monster hunters have someone on their side like Maryse Boudreaux, who has three powerful allies in another world (who might be trustworthy, but who also have fox teeth in their smiles) and a sword that’s bound to the spirits of those – all of those – who died in slavery.

Visions dance in my head as they always do when the sword comes: a man pounding out silver with raw, cut-up feet in a mine in Peru; a woman screaming and pushing out birth blood in the bowels of a slave ship; a boy, wading to his chest in a rice field in the Carolinas.

Maryse is a young woman with a very personal history with the Klan that she doesn’t want to talk about, thank you, even though it becomes more and more obvious that she’s stuck in nightmares of the past. She’s accompanied by a fascinating cast of characters, each with their own history and way of seeing the world; Sadie with her Winchester and her tabloid conspiracy theories, explosion-expert Chef who disguised herself as a man to join the Black Rattlers regiment during World War I, Michael George the handsome proprietor of Frenchy’s Inn and a man who Maryse is more than a little bit interested in, and Nana Jean, the old Gullah-speaking woman who’s the most powerful magic user in the area, possibly in the whole South.

The title of the novella comes from the ritual practiced by the descendants of slaves. It’s part dance and part call-and-response song; it’s a celebration of history and a musical rebellion and joy and so, so much well-earned anger all at once. It’s the method Nana Jean uses to create magic to protect the community from supernatural evils like the Ku Kluxes, and from the nasty, everyday evil of lynching and mobs. This type of magic isn’t quite in conflict with the power of Maryse’s sword and the three “Aunties” who gave it to her, but it’s different enough to make Nana Jean worry about what the sword might be…doing…to Maryse.

The novella is a look at a small section of the pain caused by slavery, Jim Crow, and all the everyday atrocities that evolved from them. It’s a study of community, and family, and the different flavors of hatred and anger, and how each of them can be either useful, or small and ultimately self-destructive when it doesn’t actually create anything. And not least of all it’s about how easily the people in power can use hate to make people think that someone else is the real enemy.

It’s also a rollicking action story, with swordfights, and monster battles in the halls of a burning building. The author spins a tale with laugh out loud moments like Maryse and her compatriots bickering during a mission, and moments of true horror in the dissection lab of the mythical Night Doctors. The climactic battle has some truly chilling pictures, like the images from a black-and-white movie being projected across the body of a titanic monster that can only be described as “Lovecraftian” which, knowing what we do about H.P. Lovecraft’s attitudes towards members of other races, seems pretty damn appropriate.