…when people joke and call me Riot Baby for being born when I was, it ain’t with any kind of affection, but something more complicated…

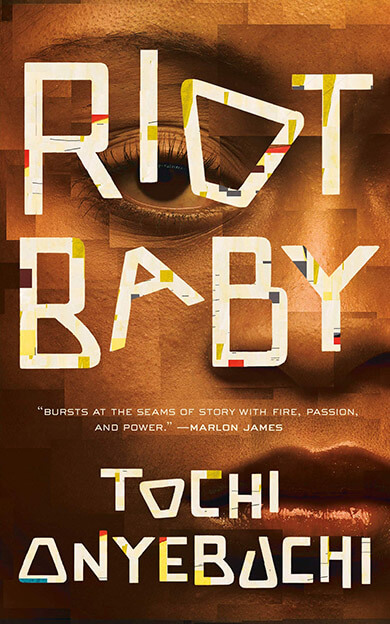

Tochi Anyebuchi’s Hugo-nominated novella starts in Los Angeles just before the Rodney King riots. Kev is born in a Los Angeles hospital in the middle of the riot, almost dying from treatment by doctors and nurses who can’t be bothered to care about the outcome of one more African American pregnancy.

Bearing witness is Kev’s older sister, Ella. It would be traumatic enough having to see all of this chaos from the inside, but Ella has also started showing the hints of a power that’s never fully explained. Her “Thing” is a gift (although she wouldn’t always call it that) which lets her see the future, experience glimpses of people’s minds just by being near them, and gives her the power to knock down walls and throw furniture around with her mind when she’s angry. And the older she gets and the more she see of the relentless injustices in the world, getting angry is something that’s starting to happen all the time.

Anyebuchi’s prose is immediate and abrupt, pulling the reader right into a blisteringly hot Los Angeles (and later Harlem), where gangbangers muscle their way onto school buses to threaten smart-alleck boys with a gun to the face, and little girls sit on the porch eating Werther’s candies while the elderly babysitter sweeps bullet casings from the night before off the driveway.

Ella is luckier than many, with a single mother who works endless shifts at the hospital to keep her and her little brother fed. But it’s still a hard enough existence that when Ella starts showing magical powers there’s nothing immediately hopeful about it. Seeing a vision of a boy from school joining the Crips, or the neighbor’s baby getting gunned down in the crossfire of a drive-by ten years from now, well, none of that feels like something out of a fairy tale, does it? In fact sometimes it doesn’t seem so much as a special talent as just having to watch over and over again what’s inevitable.

It’s not clear how much of Ella’s power is shared by Kev, but he seems to take having a super-powered big sister in stride, even while he and his mother try to keep everything quiet and normal.

Rats don’t scare Mama, but folks catching Ella doing her Thing scares her, what they’d do if they found out she could do things like make a rat’s head explode without touching, that scares her, so she smacks her upside the back of the head anyway. A just-in-case.

Ella’s powers and her relationship with her mother are starting to go more and more out of control at the same time that Kev is being pulled (not completely unwillingly) into the company of the angry young men of their Harlem neighborhood. Kev’s chapters are street-level and frightened, but with a weird kind of confidence that actually feeds on the hostility around him. Everyday cruelty and harassment by the police are met with sneers and taunts, both sides trying to see how far the other can be pushed.

Every altercation feels a little like getting some of the power back that’s taken again and again every time there’s another unarmed civilian shot, another riot that’s brutally repressed, another stop-and-frisk(or stop and slam someone facedown into the street) just for being there. You probably didn’t need Ella’s ability to see the future to know that eventually Ella will be taking the long commute to visit her brother in Riker’s.

She worries sometimes, whenever she gets onto the Q101, that she’s turning into one of the other women or the other men coming to visit friends, brothers, sisters, wives, husbands, fathers, mothers, guardians, godparents, bullies, victims, community pillars, the man who sold their mother crack. That deadness of the face.

The gap between Kev and Ella’s lives become wider and wider as Ella learns how to use her powers, and Kev learns how to survive in prison. Ella goes to the desert to fly, she teleports around the world, she looks into the past, she walks invisibly into the Kentucky Derby to bet with other people’s money. Kev deals with the brutality of prison: exercise yard fights, cells being tossed, the constant threat of attack, solitary for months at a time.

So much of the book is Ella’s dreamlike visits to Kev and the (real? maybe?) places she teleports him to when the guards can’t see. But none of it is helping. Her powers are becoming more and more godlike but none of it is saving her brother and none of it is fixing everything that’s wrong. Her desperation and bone-deep weariness echos what I’m sure a lot of people feel when they have to watch the coverage of one more police shooting on the news and know that nothing is changing.

This isn’t a standard story with a beginning-middle-end. This is the author taking all the anger and sorrow and fierce love and one example after another of real-life news stories and splashing it all onto the page telling everyone look! This is what it’s like! This is what is going on all the time! The relentless violence, the institutionalized cruelty, the generational poverty, the indifferent medical treatment, the for-profit prison system with it’s endless fines and fees, and everyone deciding that you are the actual problem. Even the dystopian elements – the high-tech monitoring, the computer algorithms that decide where police presence is higher, the implantable chips that act like an ankle monitor with sedatives – these are all so close to what’s already possible that it’s not a question of if they’ll be invented but when.

And even if you do everything right and somehow never get on the wrong side of the law you can still be gunned down in a prayer circle for absolutely no reason.

Riot Baby is hallucinatory and disjointed, achingly real and filled with rage and a fierce hope. It has no easy answers, zero platitudes, just the conviction that the problems of race in this country are getting worse, not better (Anyebuchi mentioned in an interview that we don’t have a “broken system”, we have one that’s working exactly the way it was designed), and a dream of what it would take to right all of the wrongs, all at once.