“The unique layout of LitenVärld encourages wormholes to form between universes. These wormholes connect our stores to LitenVärlds in parallel worlds.”

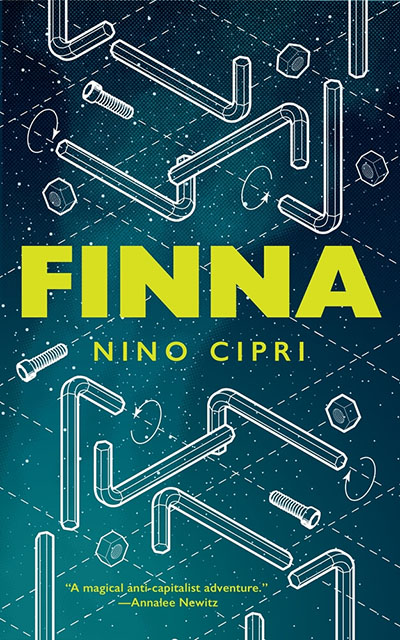

Nino Cipri’s story Finna is the last novella that was left for me to read in the Hugo nominations for 2021. At 92 pages it’s also the shortest novella, and the most weirdly lighthearted. The concept is irresistible, the characters are humorous and at the same time believably real. The plot goes from anti-capitalist satire, to slice-of-life struggles with mental health and identity, to some surprisingly nightmarish sections involving cloned corporate workers, carnivorous furniture (you heard me), and the constant danger of space and time collapsing.

The first few days after a bad break-up can be pretty rough. Having to report to your low-wage job on what should have been your day off and finding out you’re sharing a shift with your ex is worse. The both of you getting volunteered for a dangerous mission to rescue an elderly customer who’s wandered into another dimension that’s connected to ours via wormholes that randomly appear in the mega-store’s labyrinth of kitschy furniture and twee bedroom designs, well that’s…that’s not normal. Is it?

“So for anyone who hasn’t already heard, we’ve got a maskhål.”

I’ve always loved the concept of places that are so confusing they sometimes open into another dimension. My favorite example of this is Neil Gaiman’s character Destiny, and being able to find his world only by getting lost in a labyrinth. The concept is similar here, except that maskhåls (wormholes) to other dimensions appear in LitenVärld stores so frequently that they actually have a corporate policy for how to deal with them. And a corporate-designed device called a “Finna” that can point to a person who’s stepped through a maskhål and gotten lost. And corporate cutbacks that mean each individual store is entirely on their own when a maskhål appears.

Cipri takes this admittedly fantastical concept and sets it inside a corporate world that they take right up to the edge of ridiculous while still being recognizable to anyone who’s had to work a soul-crushing job in a big-box store. I could sympathize with the annoyance/boredom/despair of the employees having to sit through an emergency meeting, watching a “helpful” presentation on technology that hasn’t been updated since the video was recorded. (A VHS tape? Seriously? Who even has a VHS player anymore?) And I can just picture having to pretend to be enthusiastic for an endless parade of shoppers trying to find the one out of dozens of overly-detailed decorating themes that really defined them as a person.

Each room was alien and strange relative to the one before it. Strung together, they resembled an ugly necklace designed by a child, picking out the most garish beads to thread.

The LitenVärld store itself is delightfully weird. I loved all of the names for the different mock-up rooms: Nihilist Bachelor Cube, Parental Basement Dweller, Pan-Asian Appropriating White Yoga Instructor. And things get even weirder in the LitenVärlds that are found on the other side of the wormhole.

The trees themselves sprawled low and wide across the grass, with branches that twined into the shapes of chairs and tables. Cookware sprouted up from the ground like sharp, metallic flowers. Two massive butterflies chased each other, each wing the size of a paperback, and with a pattern that looked weirdly like fabric swatches.

What keeps all of this from completely flying off into the wild blue yonder of fantasy and anti-consumerism is the relationship between the main character Ava and her ex Jules. Ava suffers from almost-crippling anxiety and depression, Jules is trans and born to immigrant parents (Jules’s pronoun is They, but try getting the average big-box consumer to get that nuance right.) The two of them bonded and eventually formed a relationship at least partly out of their shared outsider-status. Unfortunately their all-too-human issues with trust and acceptance and the impulse to either fix a problem or run away from it was also what led to the breakup. It’s a surprisingly mundane situation, one where there’s no good guy or bad guy, just two people who are now unhappy apart because they couldn’t figure out how to continue being happy together.

Heartache felt like a persistent hangover: lethargy, a headache, an unshakeable belief in the cruelty of the world, drifting outside of time. It was hard to keep up the bullshit facade of industriousness when she felt entirely dead inside.

This is not the story that happens with maybe 1% of relationships, where the estranged couple are happily reconciled and move back in together after they’ve gone through an adventure. This is the story of the other 99%, where two people have to redefine their relationship, trying to build something new between them that’s based on what the other person is rather than what they wanted or needed them to be.

It’s just that in this story they have to do this while negotiating alternate worlds of feral customer service reps, battle-readouts made of levitating sand, an alternate-world LitenVärld that’s entirely water, with an entire bazaar set aboard a giant submarine (I do love a good otherworldly bazaar). There are some surprisingly nail-biting chases, one of which being a reality-bending retreat through a collapsing maskhål. I kept thinking while reading this that there was just too much world to fit into one 92-page story. And I was right; book 2 of the “LitenVerse” came out in April, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the author had quite a few more trips through the maskhåls planned.