“I am the Father of Mysteries.” He spoke in deeply accented English. “The Walker of the Path of Wisdom. The Traveler of Worlds. Named mystic and madman. Spoken in reverence and curse. I am the one you seek. I am al-Jahiz. And I have returned.”

We’ve reviewed quite a few short stories by P. Djèlí Clark, all of which have been nominated for awards. Last May he released his first full-length novel, and right out of the gate it’s been included as one of the best books of 2021 by both Goodreads and Amazon. The book is part of his alternate-reality Cairo series, and features returning characters from his short story “A Dead Djinn in Cairo”.

As the youngest female agent in the Ministry of Alchemy, Enchantments and Supernatural Entities (and one of the best agents, period) Fatma el-Sha’arawi was the natural choice to investigate a mysterious figure claiming to be al-Jahiz, the man who opened the door to the supernatural forty years ago and then disappeared without a trace. The imposter (I mean, it has to be an imposter, right?) is spreading a trail of destruction and unrest and seems to be determined to tear down everything that’s been built in the last few decades.

But first things first, Fatma is outraged to find out that she’s been assigned a fresh-faced rookie agent to supervise. The very last thing that Fatma – who’s made quite a reputation for herself as an extremely determined I Work Alone – needs or wants is a partner.

Don’t worry if you haven’t had a chance to read Clark’s previous story featuring Fatma (where she saves the entire world from an insane angel), since Clark establishes the hell out of her character in her very first scene. Confident, quick on her feet, wearing a dapper suits and impossible to intimidate, Fatma wraps up a dangerous undercover mission and demonstrates that the story of Aladdin is probably BS, because opening up a sealed container and demanding a wish from the the djinn inside will never be anything other than a Really Bad Idea.

I mentioned this in my review of “The Haunting of Tram Car 015”, but I really need to bring up again how bewitching Clark’s portrayal of Cairo is here. Forget the stereotypes; thinking that every person in Egypt wears the same robes and follows the same religion and speaks the same language is about as silly as thinking that everyone in America wears a cowboy hat. The Cairo we see here is vibrant, multi-layered, filled with a dazzling variety of fashions and food and architecture and worship. Just like in the present day, accents and religious affiliation and family relationships and mythology all morph over the course of a lifetime or several centuries. This is more than a Cairo with steampunk and djinn.

And also it has steampunk and djinn.

Djinn with the heads of gazelles or birds. Djinn small as children, others well over ten feet. Blue djinn and red or black and marble-skinned. Translucent elementals of ice and others made up of puffs of clouds. Djinn with skin like grass or rock. With teeth and claws, some with two heads, and as many arms as six.

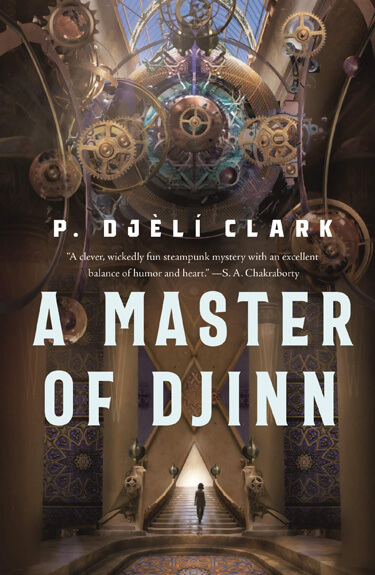

When al-Jahiz opened a door to the supernatural it changed society in ways that are still rippling outward. British colonialism was pushed out of Egypt by sheer force of magic, and it’s slowly losing its grip on every other country that’s embraced the new powers, and new machinery, and most especially new people, like the Djinn. It’s perfectly normal to see a goat-headed djinn reading a newspaper on the tram, or to have a towering blue-skinned horned figure appear to threaten everyone with a terrifying display of power, or to make their next move in a chess game with an elderly restaurant owner. Djinn-designed architecture is almost commonplace, travel frequently takes place via high-tech airships, and the building that houses the Ministry of Alchemy, Enchantments and Supernatural Entities is run by a towering steampunk mechanism.

She spared an upward glance, where giant iron gears and orbs spun beneath the glass dome, like some clockwork orrery. It was, in fact, the building’s brain: mechanical ingenuity forged by djinn. Smaller replicas allowed aerial trams to self-pilot without the need of a driver. This one helped to run the entire Ministry. The building was alive. She tipped her bowler in good morning to it as well.

As you can probably guess from having female agents in 1912, the position of women in Cairene society is pretty advanced as well. Women have the right to vote, and to work in traditionally male-dominated industries. And in a refreshing change of pace for a female-centric story in a society mostly run by men, Fatma and her new partner Hadia spend a minimal amount of time dealing with attitudes of “run along and let the menfolk handle this”. Most of that is in the past, and Fatma has come out of that with a penchant for fancy suits, a snappy bowler, and an attitude that lets her shut down arguments with a glare. Hadia meanwhile is all sweetness and enthusiasm, a devout Muslim who can handle herself in a fight and knows how to throw scripture right into the teeth of someone who thinks they can make a racist comment without getting called out for it.

And yes, there are still some prejudices that people have to deal with in this glittering Cairo, much like there is everywhere. The attitude of any of the British characters goes from mildly annoying to downright infuriating (especially the idea that the original al-Jahiz must have been from a secret race of Caucasians. Can’t have powerful and intelligent people coming from foreigners, oh no, they must have been white people all along.) Hadia is still chafing at the experience of being the only woman in her class at the academy. For Fatma, it’s not explicitly stated, but she has to keep her relationship with her friend/former associate/occasional lover/it’s complicated Siti on the down low. And Siti herself has the double whammy of an Egyptian society that looks down on anyone Soudanese or Nubian and dealing with prejudice against her chosen religion as a follower of one of the forgotten gods. She’s absolutely not going to let any of that bother her, but it’s got to be exhausting sometimes.

(Siti, by the way, is one of a long line of kick-ass female characters I adore, one with a smart-alack attitude and zero fucks to give. She’s the closest thing in the book to a secret agent, she inserts herself into Fatma’s investigation and Fatma’s life without a whole lot of effort. She worships the goddess Sekhmet, and she reminds me a tiny bit of Sekhmet from The Wicked + The Divine, although she’s not quite as amoral and destructive. Usually.)

“So what is it you do at the temple?”

“I look after things. Fix things. Put things together.” Siti flashed a sharp smile. “Sometimes, if I’m lucky, I get to break things too.”

The way magic blends into historical events isn’t just fascinating here, it’s fun. Every few pages there’s another delightful image: a new mooring mast for airships to dock right next to the pyramids of Giza. An open-air marketplace of tents and spices and coffee stands and replacement parts for mechanical servants (I love a good marketplace setting.) A members-only underground club with enchanted champagne and New Orleans jazz musicians (also love me a secret jazz club). An awe-inspiring library in the basement of the Ministry (I really really love a good library, especially one with a djinn for a librarian.) Kaiser Wilhelm II, with a tiny goblin advisor on his shoulder. You heard me.

The book starts with the terrifying death of every member of a secret brotherhood at once. It quickly spirals outward into political intrigue, and a gang of female thieves, and a chain-smoking crocodile acolyte who can not stop being creepy, and mechanical angels, and just how weird it can be to try to have a nice cup of tea in an illusion-djinn’s apartment. It’s one of the best examples out there of Urban Fantasy, but at its core this is very much a Murder Mystery.

With steampunk and djinn.

Cover artwork by Stephan Martiniere