“…nothing.”

That is what the fortune teller says when the girl gets up the courage to ask “Will you tell me my fate?” Her favored older brother Zhu Chongba is destined for greatness; the only surviving daughter of the Zhu family is destined to starve to death along with most of her village.

But then disaster strikes, and the girl realizes she has an impossible chance: to steal her brother’s fate and make it her own.

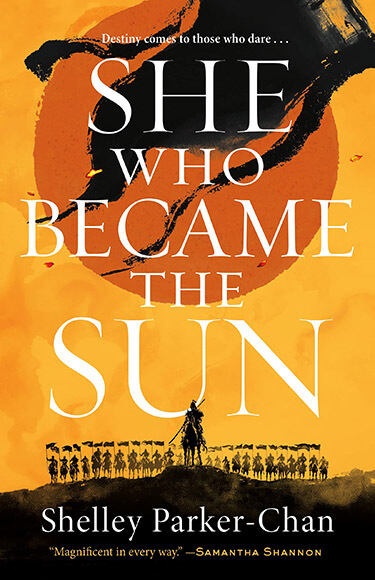

Shelley Parker-Chan’s Hugo-nominated book retells the story of a well-known Chinese warrior-monk, but with a few slight alterations. In this version of 14th-Century China, ghosts are most definitely real, and leaders can glow with supernatural light as proof of their right to rule. The biggest change is that the founder of the Ming Dynasty is actually his younger sister, who’s decided that she’s not going to just survive, she’s going claim the Mandate of Heaven for herself.

Her brother’s face swam before her eyes, kingly with entitlement. Useless girl.

Some new hardness inside her answered: I’ll be better at being you than you ever were.

It’s pretty harrowing to be a girl in Mongol-occupied China. Women have zero power, and are either used as barter or allowed to starve (if not outright murdered) by families trying to make sure their male children lived. And believe it or not, the girl now known as Zhu Chongba has zero interest in changing things for all women. To pass as male she has to be flawlessly male, both to her fellow humans and to Heaven itself. If she does anything that her entitled other brother wouldn’t, even having sympathy for a fellow woman, she runs the risk of Heaven realizing that she was still the person who’s destiny was “nothing”

Her stomach shrank as she felt the resurgence of her oldest fear: that if she prayed, Heaven would hear her voice and know it was the wrong one.

Fortunately Zhu is both intelligent and freaking clever. Half of the fun of this book is seeing what she comes up with next to survive another day and claw towards her stolen destiny. Whether it’s getting a place in a monastery (and keeping her fellow monks from seeing under her robes. For years.) or somehow staying on the good side of manipulative politicians who are always ready to execute their rivals in truly horrible ways, Zhu (sometimes ruthlessly) keeps managing to capitalize on random chance, unbelievable luck, and other people’s willful blindness.

The novel branches into several different viewpoints, most notably the eunuch-general Ouyang. Despite the fact that everyone except the prince he serves treats him as a damaged thing, he’s managed to rise to a high position in the Mongol army, so you already know his story will be interesting. There’s also the Mongol prince’s half-Chinese adopted brother, who’s father only values military skills and who has zero patience for all the non-military work that goes into keeping a family wealthy and powerful (definitely a Cain and Abel thing going on there). And then there’s the fiance of a rebel general who’s too arrogant to treat anyone as a person, much less the woman he’s arranged to marry.

In fact that’s the element that all those primary characters share: not being valued for who they actually are. And you would think that would create a bond between them, since the pain from being completely dismissed by the people who despise you, and not being seen by the people who supposedly love you, is in many ways the exact same pain. But at least fifty percent of the time, recognizing themselves in someone else just makes them hate that person even more. Ouyang and Zhu end up as equally-matched enemies bent on each other’s destruction almost before they learn the other exists.

The fact that the Mongols and the Chinese rebel army are fighting for their existence doesn’t stop the political infighting. The various players are often so focused on their own schemes and resentments that they sabotage any advantage their side may have. The beautiful surroundings – a monastery on a mountainside, towering palaces with interlinked gardens, a luxurious Imperial hunting camp on the plains – can be the scenes of life-and-death confrontations, sometimes over something as trivial as a “joke”.

Now, usually I get a little nervous with confrontations, waiting for someone to say something unforgivable, or at least very, very embarrassing. I’m not sure how Parker-Chan managed it, but I found myself looking forward to every confrontation here, every military strategy session or dust-up between family members. There’s something delicious about waiting for the next meeting, wondering who was going to make a fool of themselves without realizing it, or who”s going to lose their temper for a really really bad reason, or who’s going to put a plan in motion that’s so complex we won’t even know what the goal is until the moment someone starts bleeding.

The reader can guess from the book’s description, heck, from the title, that Zhu is going to rise to dizzying heights. What isn’t clear is what it will cost. What it will cost any of the characters, whether they’re acting out of love or fury or white-hot will. Parker-Chan lightens the mood with scenes of tenderness, or love, or sometimes humor (Zhu learning to ride a horse is one of my favorite scenes), but none of the characters are trying to avoid their own suffering. Quite the opposite, in fact. Getting close enough to your enemies for revenge means feeling all the pain they feel when everything finally falls in place. Being willing to do whatever it takes for power and greatness means everyone close to you has to take second place in your heart.

This particular time period in Chinese history, existing in the last gasps of Mongol rule but before the beginning of one of the most famous Chinese dynastys (kind of like how Zhu and Ouyang exist in between the rigidly-defined roles of “male” and “female”) has enough drama and turmoil going on to fill at least a dozen Chinese TV drama-style books. So it’s a good thing that Parker-Chan is already working on the sequel to this one.