The dead don’t walk. Except, sometimes, when they do.

It’s a day early for my usual weekly book review, but Halloween is the perfect day to review a new(ish) novella by T. Kingfisher that was inspired by Edgar Allen Poe’s “Fall of the House of Usher”.

It’s not one of my favorite Poe short stories (that would be “Hop-Frog”, which probably says something about me), but I still think “Fall of the House of Usher” is a masterwork of atmospheric dread and gradually increasing terror. It’s a little light on explanations though, and Kingfisher apparently wanted to explore some theories about what might have caused the mysterious illness that led to Madeline Usher being prematurely sealed into the crypt. All the elements are there in the original story; the unmoving water of the tarn, the grand house that’s been decaying for generations. The fungus. The whole property is covered with fungal growth, that can’t be healthy.

Mosses coated the edges of the stones and more of the stinking redgills pushed up in obscene little lumps. The house squatted over it like the largest mushroom of them all.

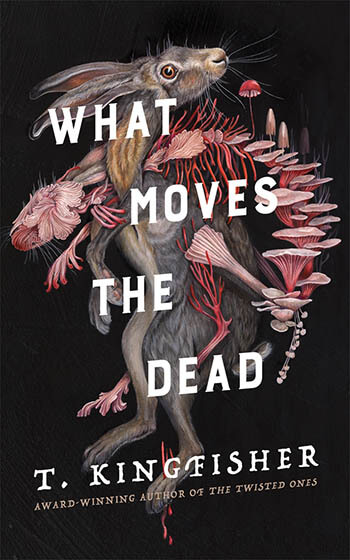

Some things can be frightening depending on how they’re described: a long illness, an isolated house, the loneliness of being the last of your family. Other things are just instinctively horrible. Fungus, for instance. Fungi can be nasty; weird growths sprouting like tumors, flesh-like forms covering the ground or crawling over the walls. I can imagine some of them actually having, uck, warmth, like skin with a fever, or an alien biology.

Something else that feels instinctively scary are, oddly enough, hares. Not rabbits, not bunnies, but the long-legged, thousand-yard-stare hares. Mostly solitary, they sometimes look like they know things that humans probably wouldn’t be comfortable learning.

Now imagine what Kingfisher can do in a story where fungal growths are the invading force in a mostly empty wilderness, and hares are the sign that something is very, very wrong.

This one was so still that if the breeze had not moved its fur, I would think it might be dead. It did not even twitch its ears. I had not seen it blink.

The nameless narrator of Poe’s story has been replaced by retired soldier Alex Easton, lately of the Galacian army. Kingfisher has invented an entire new society in Gallacia and their proud but usually not very effective army. Easton makes for a much more interesting protagonist than Poe’s narrator; they have a lot of experience with both the best and the worst that humanity has to offer, and they’re far enough removed from their time in the wars that the trauma is mostly background noise. They’ve also dealt with other people’s ignorance of how the whole Gallacian “sworn soldier” thing works that they can mostly laugh off intrusive questions about pronouns. Mostly.

They ask questions, but what they really want to know is what’s in your pants and, by extension, who’s in your bed.

Easton rides to the House of Usher in response to their old friend Madeline’s letter, fully expecting that she’s not going to last another few months. They’re joined by a sometimes annoying but charming American doctor, and a brash English mycologist woman who might have a famous niece. It’s a Kingfisher story, so there are a lot of fun moments like everyone getting drunk on horrible Gallacian liquor, or a teasing conversation at dinner time where everyone points out what is and isn’t a deer. But the humor quickly fades when it becomes obvious that the wildlife in the area is acting very strangely, Madeline’s brother Roderick is terrified of something, and Madeline’s illness is…not normal.

Madeline’s lips pulled up at the corners in a terrible parody of good humor, her mouth stretching painfully wide, her jaw dropped so far that it looked almost like a scream. Above that awful grin, her eyes were as flat and dead as stones.

This is a tasty piece of gothic horror, perfect to read on a blustery Halloween night. It’s also a great excuse to go back and re-read Poe’s original story. I’d totally forgotten until recently that the first time I tried reading “The Fall of the House of Usher” I’d skipped right to the end. I ended up being convinced for years that the Ushers had been such horrible people that the house was swallowed up by the earth as a punishment, instead of some weird symbiotic relationship between the dying family and the house. It’s not quite the same kind of relationship that’s revealed in Kingfisher’s story though; if it had been, you could imagine the nameless narrator pausing in his terrified retreat to set the place on fire, just to be safe.