The gates of the Institute swung open. The car turned down the driveway, and the Whitethorn Institute swallowed another incoming student alive.

It’s been months since Cora returned from The Moors, and she still can’t sleep through the night without nightmares, still can’t clean her skin from the rainbow sheen that the Drowned Gods gave her when they were trying to make her their own. The former (current? It’s complicated) mermaid can’t even enjoy swimming anymore without hearing the whispers of the Drowned Gods trying to drag her back to them. Life in Eleanor West’s Home for Wayward Children isn’t working, what she needs is a place where she can learn to forget. A place to forget The Moors, forget The Trenches where she was actually happy, forget ever being a mermaid. A place like the rival school The Whitethorn Institute.

Cora hasn’t been in Whitethorn for more than five minutes before she realizes she’s made a terrible mistake.

…this place was so big and so cold, and this was just a different way to drown.

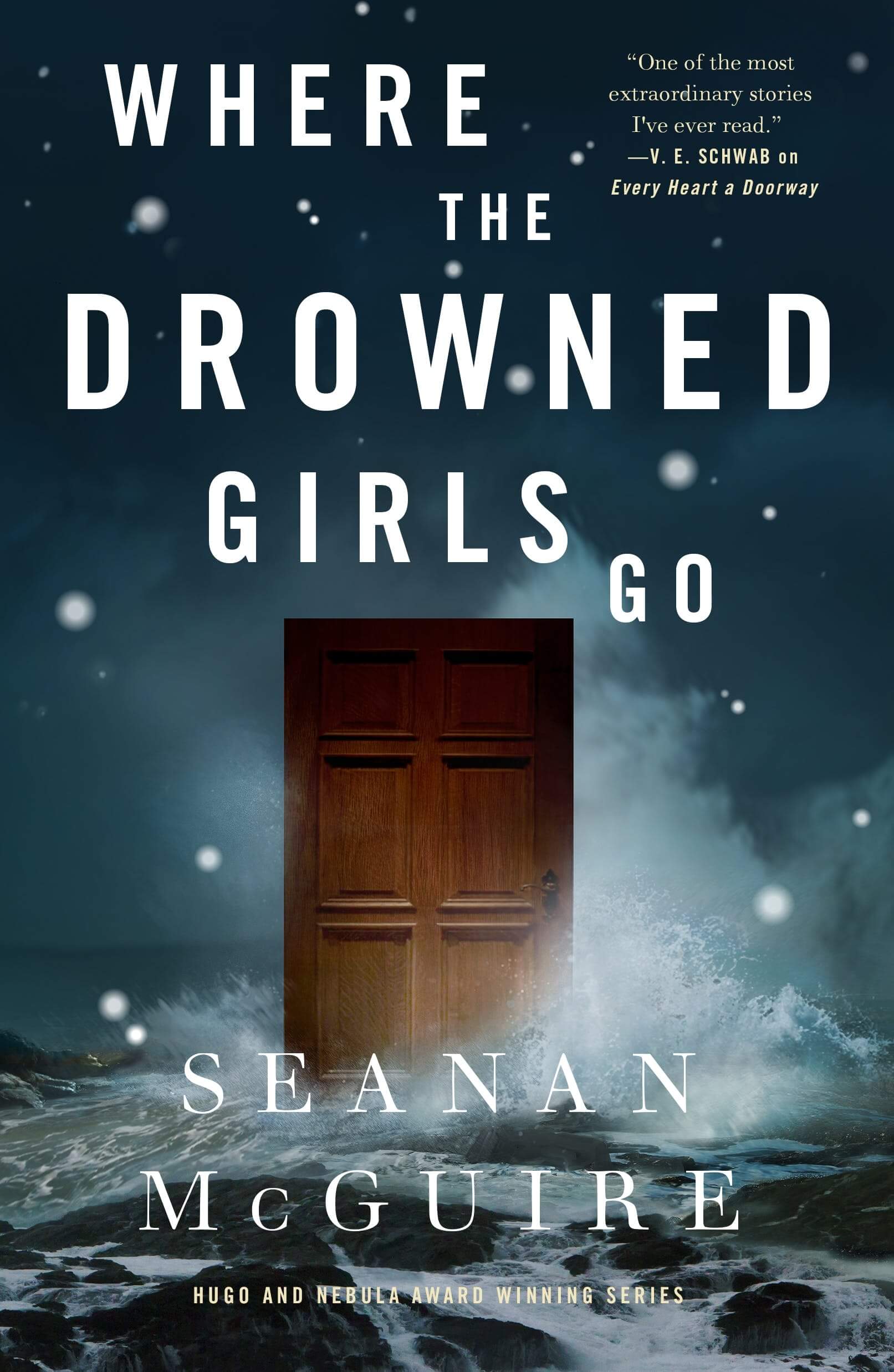

It’s been almost two years since the last time I reviewed one of the Wayward Children books, at least partly because it’s a little grim going into a story knowing that any happiness the children have in the world they find behind a door will soon be lost. Eventually they’ll be pulled back to the “real” world and spend the rest of their lives trying to learn how to be happy again. We never see Cora’s world of The Trenches firsthand, but we do see glimpses of the life she had before, as a teenager in a world where it’s perfectly acceptable to be intolerant of fat people. Trigger warnings for bullying and a suicide attempt, because it’s all pretty harrowing.

She’d gone on her first diet when she was eight years old.

In a perfect world Cora would be celebrated for being bright, friendly, pretty, and athletic. In reality she’s constantly judged for “not trying hard enough to be thin”. No matter how much she diets, or exercises, or avoids sugar of any kind, her body’s chemistry simply won’t let her get anywhere close to slender. It once got to the point where social services were called because she spent three weeks not eating until she passed out and her school thought her parents were starving her. And after all of that she was still fat. Deliberately trying to drown herself to escape the relentless criticism felt like Cora’s only option.

Seanan McGuire uses these books to explore all the ways children can feel isolated and unhappy. In pretty much every case that unhappiness comes from someone – family, acquaintances, the world, themselves – trying to shape them into something they “should” be instead of accepting them for who they “are”. Cora’s suicide attempt opened a door to The Trenches and her transformation into a mermaid. Surrounded by fellow merpeople who loved everything about her, becoming someone who’s shape was an asset, Cora finally found acceptance…only to be dragged back to her birth world and the company of schoolmates who could now torment her for her mermaid-blue hair as well as her weight. And then her traumatizing adventure in The Moors took away her last comfort, so it’s no wonder Cora decided a school that would shape her into something “normal” was better than one that tried to help her adjust to being “different”.

“Please. I want to wash the Moors off my skin. I want to drain the Drowned Gods out of my soul. I can’t do either of these things here, where I’m expected to dwell and dwell and dwell on what happened. Please. You have to let me go.”

I don’t know about “normal”, but The Whitethorn Institute promises to take in children who have traveled through doors and remove all of their pesky differences until everyone is the same. Entirely the same. Reduced to a beige, inoffensive sameness. Children who traveled to Nonsense worlds have strict order; children who traveled to Logic worlds have variable schedules and are forbidden to tidy things. If you crave sweets you get vegetables, if you want vegetables you get waffles with whipped cream. Everything you liked about your World, that you like about yourself in your World, is whittled away. It’s almost as if you’re not being cured or fixed to only want normal things, you’re being forced into a fucked-up belief system that punishes you for wanting anything at all.

You can draw parallels between Whitethorn and many, many other “reeducation” schools. Conversion therapy. Scared-straight institutions. Military camps for gentle boys and Magdalene Laundries for problem girls. I’m sure a lot of them would insist, like Whitethorn does, that many students choose to be there. Cora’s equally sure that isn’t the case, that the school is a last-ditch effort by parents to redo whatever it is about their children’s personality they find sinful, or sick, or just plain embarrassing.

And really, if someone did choose to be there, like Cora, isn’t that in many ways a little worse? That the world could beat someone down to the point that they’re desperate for a “cure”. Only to find out that the cure is just lying to yourself enough times that you believe it, and it’s administered by staff that are capable of any type of cruelty because they honestly and truly believe that the suffering they cause is for your own good.

“…the people here think they’re helping us. They think they’re heroes and we’re monsters, and because they believe it all the way down to the base of them, they can do almost anything and feel like they’re doing the right thing.”

We get to see a couple of familiar faces in this particular quest-gone-wrong, one of whom is a little downheartening (I had hoped for a better outcome after the end of their story), and another who I shouldn’t name but always brightens things up with her own brand of madcap bravery, escape attempts, and kindness. (Okay, yes, it’s Sumi.) And what also keeps this story from being too dark is the theme of who actually deserves to escape. I know it’s a little trite to say that “hurt people hurt people”, but it follows that if you can understand why they’re hurting, then there’s a chance they can be, not fixed, but maybe rescued. Even if the person doing the rescuing is themselves.