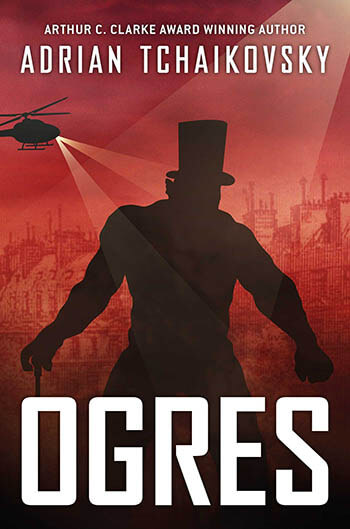

They’ve always been there, your Masters the ogres.

The start of Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Hugo-nominated novella has all the makings of a Robin Hood-style adventure. The beloved but mischievous son of the village headman befriends the merry band of outlaws who live in the woods (away from the control of the wealthy Landlords) and who dream of freeing the villagers from poverty.

Except…the Landlords are all towering Ogres, in a land where they’re the only ones who can digest or even touch meat. Roben’s band of outlaws are anything but merry, and they have enough trouble trying to get food for themselves and not freeze to death in the winter to worry about giving to the poor. And headman’s son Torquell doesn’t have any interest in the outlaw life beyond having a group of friends listen to his stories, and maybe ducking his responsibilities for a few hours.

Torquell could have probably skated through his entire life like this, but it only takes one impulsive act to piss off the wrong ogre, and then everything is changed for the worse, forever.

He’s grinning, and when he sees you’ve just about worked it out, that grin gets so wide you half imagine the top of his head just falling off.

The novella has an interesting style that instantly pulled me in and meant I finished the whole thing in less than a couple of days. It’s a sing-song, storytelling tone, and it’s told in the second person, being narrated to Torquell as he’s going through what’s basically his hero’s journey. But while the style sometimes feels a little like a fairy tale, what Torquell (and by extension everyone around him) goes through is not for children. The fable-like setting is soon invaded with cars and trains and weapons of mass destruction. The ogres have no problem with murder, rape, public execution, and every other action people can commit when they have the power of life and death over their subjects. The worst of it is told as dryly and clinically as possible, letting the reader imagine everything that isn’t said out loud.

He beats you. We won’t dwell on it.

Torquell’s path to becoming a hero and revolutionist is different from all the other outlaws trying to escape the ogres because he’s determined to find out why and how. The pastors say the ogres are put in place by God, but what could have happened to make that the case when the ogres are so vastly outnumbered? Torquell knows he needs to get the answer, because the one thing that will make everyone rebel is if he can tell them that rulership wasn’t appointed, it was stolen.

Tchaikovsky goes down some uncomfortable paths when talking about change, especially when it’s change that’s being implemented by law, and most especially when it’s change that’s being forced “for the good of everyone”. Yes, hard choices have to be made when the lives of millions of people are at risk. But you always have to ask yourself who’s making the decision, and how much easier is it going to be afterward for the people in charge to say “Well, we’ve gone this far, might as well go a little further…”

Probably the darkest part of the story isn’t about the ruling powers, it’s about revolution, and just how…unlikely it is. A revolutionist is facing a superior power, so the odds of failure are always higher than the odds of success. The leader of a rebellion has to make even more hard decisions, and to keep going ahead knowing that they could do everything right and still fail. After all, there’s really only one way to win, and an infinite number of ways to lose just by saying, “Would it be so bad if we just give in on this one thing?”