The trees were full of crows and the woods were full of madmen. The pit was full of bones and her hands were full of wires.

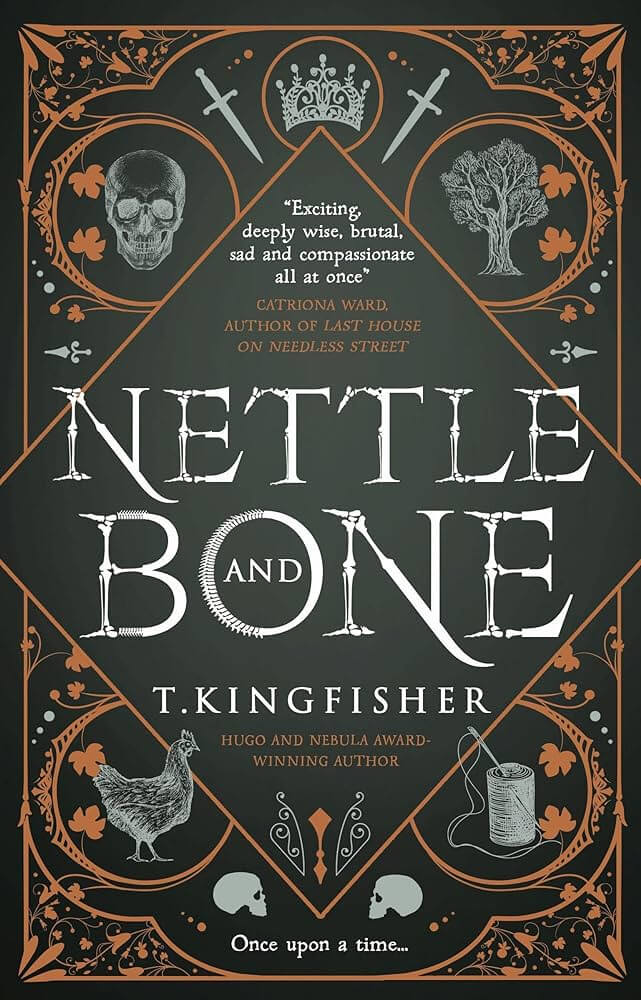

T. Kingfisher’s Hugo-nominated novel starts with the action already in process as Marra – mostly a princess and almost a nun – works to complete one of three impossible tasks: sew a cloak of owlcloth and nettles, build a dog of cursed bones, and catch moonlight in a jar of clay. It sounds like a standard fairy tale adventure, but in this case the princess isn’t trying to earn the hand of a prince, she’s trying to earn his death.

Like a lot of Kingfisher’s characters, Marra is an everyday sort of person who is shocked to find herself doing something as unlikely as planning an assassination. As the youngest daughter of the Harbor Kingdom royal family, she isn’t in line for succession and doesn’t have a lot of talent at, you know, being royal. When her older sister, Kania, is married off to the prince of a nearby kingdom, Marra is bundled off to a convent at a fairly young age so her sister’s new husband won’t have to worry that she might get a powerful husband herself and give birth to a rival prince.

Marra’s life at the convent is…fine? Nice even? Kingfisher excels at creating new saints, and Our Lady of Grackles is an almost elegantly simple saint who doesn’t call for a lot of ceremony or acts of devotion. Marra spends her adolescence learning to knit and embroider, sharing the duties (and occasional glass of wine) with Sister Apothecary, and just generally fading into comfortable obscurity.

So it comes as a nasty shock when she goes with her Queen mother to the birth of Kania’s first child and finds out what her sister’s life has been like.

“Listen,” hissed Kania. “Listen! If I die, don’t let her marry you off to the prince. Run away. Ruin yourself. Whatever it takes. Don’t let her drag you into this hell along with us.”

It’s an impossible situation. Kania’s marriage to the prince of the Northern Kingdom is the only thing keeping the Harbor Kingdom from being taken over by force. Prince Vorling is smart enough to abuse his wife where the bruises won’t show, and to hold himself back at least a little while she’s pregnant, but it wouldn’t occur to him in a million years to stop beating her. Kania can protect herself by being constantly pregnant, until that kills her, or until the Prince loses his temper enough to forget that he needs her alive to produce an heir. It’s happened before. Killing the Prince is the only way forward, and in desperation Marra sneaks away from the convent to get a spell from a dust-wife (think graveyard witch, with a Cottage Core aesthetic and lots of chickens.)

And this is where an already fun book really starts to shine, because the nameless dust-wife is powerful, and fearless enough to face down spiteful ghosts and angry fairies alike. She’s also grumpy, empathic, and has a habit of treating impossible things like everyday annoyances, which is always a delight. It’s especially fun when dealing with her prize hen who “has a demon in her”, and that’s not even a euphemism.

“How did you get a demon in your chicken?”

“The usual way. Couldn’t put it in the rooster. That’s how you get basilisks.”

Kingfisher loves to weave in all kinds of interesting tidbits from the real world into her books; the intricacies of tapestries, or spinning, or embroidery for example. But she also takes a good hard look at elements from fairy tales and starts asking questions. Why do people asking favors from a witch have to complete impossible tasks? What would it really be like to make a cloak out of stinging nettle wool? Most of the questions revolve around the concept of fairy godmothers, how they’re made, why they each give different kinds of gifts when they bless a child, and all of the problems that can be solved (or created) with how the blessings are worded. Marra’s biggest question though is what is the point of godmothers in a world where horrible things keep happening.

Nothing is fair, except that we try to make it so. That’s the point of humans, maybe, to fix things the gods haven’t managed.

Questions about the morality of suffering are often followed by random hilarious scenes, like a frazzled mother giving directions in between threats to her oblivious toddler (“The godmother, she’s very kind – I swear to the saints, Owen I will take you to market and sell you for a three-legged goat!”) Marra’s travels take her from the convent, to the Blistered Lands, to a small clean house owned by a woman with a terrifying puppet, to a seemingly endless underground maze guarded by a horrifying curse, with a side trip to a bustling goblin market. (I do love a fantasy marketplace, and this book’s goblin market is one of the more menacing examples.)

Along the way, Mara gathers an unlikely group of comrades: the dust-wife with a demon-chicken riding her staff, a distractingly handsome murderer, a bone-dog who’s the Bestest Boy and I will not be taking questions at this time, and a sweet but overwhelmed woman who carries a baby rooster next to her cleavage. There are a few people with motivations I didn’t expect, a shockingly poignant scene involving a cup of tea, and a resolution to the quest that ended on a perfect note; I actually thought “OutSTANDING” when I saw how the characters threaded that particular needle. I may have to re-read Summer in Orcus to be sure, but this may be my new favorite Kingfisher creation.