“What is it that makes a true hero?”

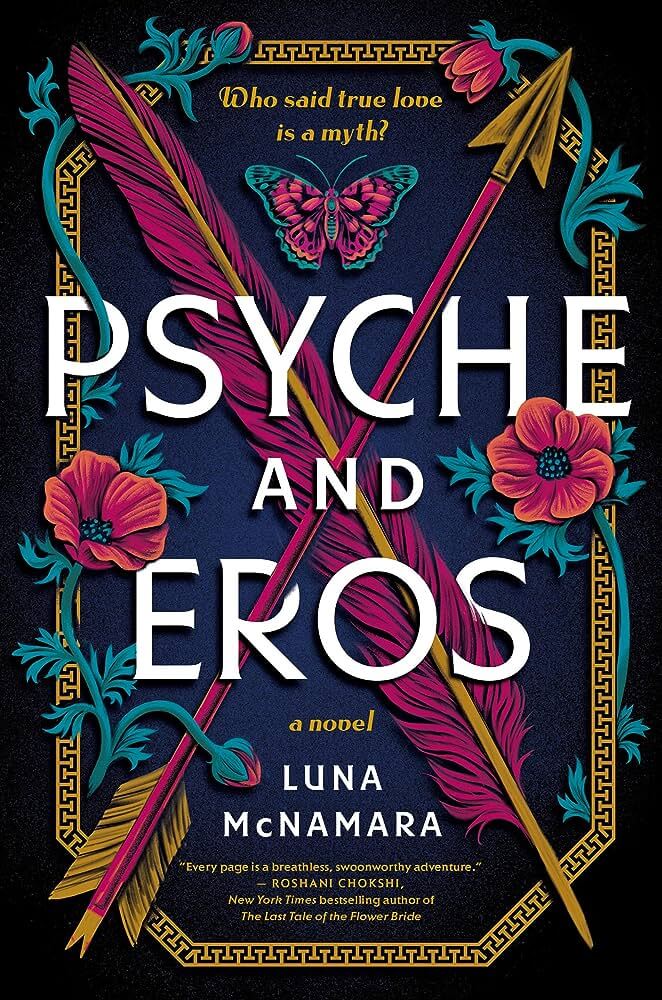

The Hugo award ceremony isn’t until October 21st, so I’m going to take a quick break to read something I bought months ago. Luna McNamara’s debut novel retells the myth of Eros and Psyche, with some very important differences.

“Your child will conquer a monster feared by the gods themselves.”

This was the prophecy that the Oracle at Delphi gave to the King of Mycenae about his unborn child. So it was something of a shock when that child ended up being female. It was a time when unwanted children (especially girls) were often left to die in the wilderness. Instead, in what could only be described as a miracle, Alkaios looked into his daughter Psyche’s eyes and decided he loved her so much that he would raise her to be the hero she was prophesied to be.

Anyone who’s read this column regularly knows I love a good retold fairy tale. And this book is just candy for me, because it’s not only a retelling of one myth, it’s a retelling that intersects with many, many, other myths, sometimes in ways that lets a famous figure sit down and tell the story of yet another myth. The viewpoint alternates between Eros and Psyche, future lovers who couldn’t be farther apart when the story starts, and who both have a completely different view of the heroes of legend.

Eros’s story begins at the very beginning of the world; this version of the god of love is actually older than his (adoptive) mother Aphrodite. As a primordial god he’s had a lot of time to learn what his power can do. He’s also had enough time to be completely disillusioned by everything: love (something which has a habit of spreading outside of his control), the gods (and how his good intentions have often made things worse), and most especially the humans who either ignore his gifts or use them to hurt each other more than they were already doing.

Prometheus had designed humanity in the gods’ image, but he had only succeeded in wrapping all our worst traits in their flimsy mortal shells.

While Eros spends centuries in isolation with his cats and his peacocks in a fantastical mountainside castle built by the goddess Gaia, Psyche grows up as a princess with the best training a royal family can provide. Her trainer is Atalanta for crying out loud, an aging hero of myth who teaches Psyche how to kill monsters, and who Psyche grows to love. (There are some amazingly poignant moments in this book, and Atalanta is involved with more than one of them.) The gruff teacher can sometimes be persuaded to tell Psyche stories of her own life as a hero, and her experience and advice about love and marriage is part of what makes Psyche very wary about the whole thing.

And Psyche has good reasons to feel this way, because the book returns many times to the concept of what women in her time experience, what they have to endure. Imagine how miserable Helen would have to be to throw away her marriage for Paris. Think about Iphigenia and her bully of a military father. Look at Medusa’s story, her life and her transformation and her death and tell me how any of that is fair. And sure, there are some female characters who buck the trend (McNamara’s version of Persephone, Queen of the Underworld, has agency, and it’s amazing) but for the most part Psyche knows that her role is to marry someone to be the king of Mycenae, and she’s afraid the best she can hope for is a husband who will permit her to continue being a hero.

Then Eros’s best friend Zephyrus kidnaps Psyche and takes her to a faraway castle and a husband who’s never allowed to show her his face and it’s…fine?

Though I had not found my husband in the usual manner, it seemed that in some roundabout way I had arrived at the right place.

Eros accidentally getting scratched with one of his own arrows is still part of the story, but the rest is much more complicated. Eros’s reasons for keeping his face hidden makes a lot more sense here. In fact everyone’s motivations are more believable than the original ones of spite, jealousy, and careless curiosity. (Except Aphrodite of course. She’s still the same petty, spiteful goddess who can’t stand having someone else compared to her.) In spite of their entire relationship being started with a lie, McNamara unspools a beautiful backwards romance that starts with cursed love and marriage, and moves on to two people discovering everything to value about each other.

I had loved Psyche from the moment the arrow gashed my skin, an unpleasant fact over which I had no control. But recently, I had begun to like her.

I loved all of the elements of humor in this book, like Eros being bemused that Psyche’s reaction to “you’re in danger from a terrible monster” is basically “A monster? I’m born to face a monster, tell me where it is!” Or Zephyrus being the kind of flighty, drama queen best friend who makes you want to pull your hair out but who will also come over late at night to help you bury a body. There’s also so much beautiful pathos, and panoramic visions of the Underworld, and relationships that are similar to the original myth but looked at from a different angle. (I particularly liked the ending to one conversation between Eros and Eris, it was honestly different from anything I’d expected.)

If you’re not familiar with any of the original myths then this book will surprise you. If you are familiar with the original myths then this book will still surprise you. (Especially one yikes moment that had so much lead-up and still felt like it came out of nowhere.) And I have to say that this is one of my favorite ways of retelling a myth; the kind that stays just faithful enough to be comforting, while looking into the “why” of everything and changing just enough that the reader can be surprised, and occasionally delighted.