Children of the Doors know about being mislaid…

Antoinette Ricci, better known as Antsy, returns to the world of the Wayward Children. Only this time she’s dragging along most of the main characters of the previous stories as they break the “No Quests” rule of their school for former fairy tale adventurers.

People who have read Antsy’s previous story can breathe easy, because this one is much less traumatizing. Seanan McGuire tends to alternate the Wayward children stories: the even-numbered books focus on one particular child, how they found their Door (and what they were running from), and how their heart broke when they lost it again. The odd-numbered books focus on Eleanor’s School For Wayward Children, and while they’re generally dealing with a very serious problem, they’re also light-hearted, and occasionally laugh-out-loud funny (Especially Sumi. Bless her, I highlighted too many of her quotes to share in one review).

Reading all the previous books in the series is recommended: the even-numbered stories are more stand-alone, but for this one you’ll need a lot of background information to understand who each character is, and what the world behind their particular Door involved. Anyone who doesn’t know all the backstories is going to be a little confused.

“Have you considered handing out orientation sheets before you drag people into whatever sort of club this is? she asked. “Nothing too involved. Just a little list of all the weird in-jokes and inexplicable references.”

Cora laughed. “No, but maybe we should look into writing one.”

I think this book is going to be even more required reading for future fans of the series, because we learn a lot more about quite a few things. Emily – one of the refugees from the Whitethorn Institute – talks about her world Harvest, and what the Institute stole from her. We finally hear more about why Kade never ever wants to return to the world of Prism, and how Eleanor found her Door as a child. And with Antsy’s talent for finding lost things, most especially lost Doors, we have many, many discussions about how the Doors work, why so many of the Wayward children are kicked out of their perfect World, and why the Doors only choose children in the first place.

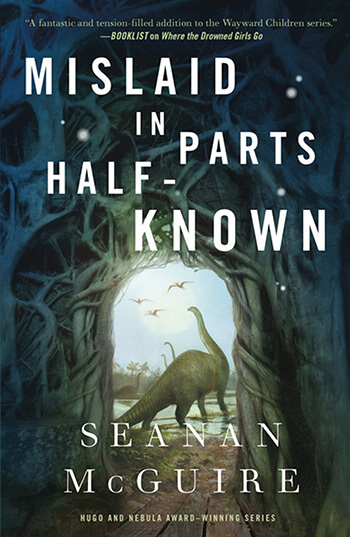

“We ask, again and again, why the doors take kids, and I think it’s a combination of things – kids are more flexible, they adjust better to things like ‘Oh hey, I’m a mermaid now’ or ‘Oh hey, that’s a dinosaur,’ or ‘Oh hey, the world is made of candy.’ They don’t argue that something can’t exist when it’s looking them right in the eye.”

(Yep, there are dinosaurs in this book. Plus the return of a familiar face, but that’s in between getting chased by dinosaurs.)

“I’m really not in the mood to meet a big, hungry lizard. Or a big, well-fed lizard, honestly. If I can just register an anti-lizard position with the court now, that would be a real time-saver.”

The reunion, and the new world, and the additional backstory, and the incident with the school’s top Mean Girl who has the ability to force Antsy find what she wants, all of that revolves around Antsy’s main quest: find the Shop Where the Lost Things Go and make sure the shopkeepers aren’t harming more children. Antsy lost a lot while working in the Store – most of her childhood and her ability to ever go back to her mother – and what’s lost in the Store is lost forever. The book’s antagonist has some Mean Girl energy of her own, and it’s tempting to give her a little leeway, considering what her actual age must be and how much she must have suffered in order for her to find her Door in the first place. She’s still appropriately two-dimensional in her malice though, which makes it that much more satisfying when some people (okay, Sumi) are ready to deliver some hard truths.

“People who’ve been hurt often think they have some sort of right to go around hurting other people, ” said Sumi. “They think trauma’s a toy to keep handing down forever. But the fact that someone hurt you and tied you up in knots doesn’t give you the right to do it to anybody else.”

Since this is one of the odd-numbered books, the story leads to a place that’s bittersweet, but also a little brighter. The fact that every individual story keeps going, and not always to the same place, means that sometimes the story about the combined friendship has to end. But at least there’s hope that at least someone, occasionally, will get a happily-ever-after.