“Welcome to the Hooflands, ” said Pansy. “We’re happy to have you, even if you being here means something’s coming.”

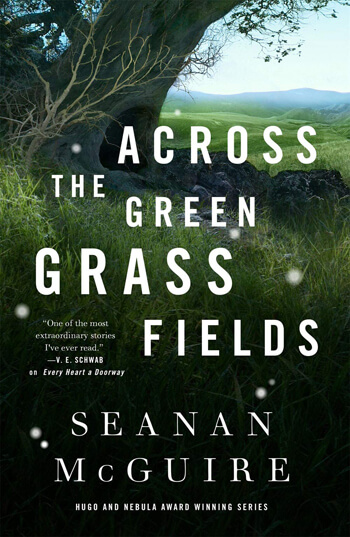

Seanan McGuire is up to Book 6 in Wayward Children, the series where children stumble across one of an infinite number of doors, each one opening to a different magical realm. This installment features the Hooflands, a world of centaurs and fauns and thousands of other hoof-footed creatures. The population of the Hooflands increases by one human girl, who finds her door when running from ten wasted years of trying to fit the mold of what a girl is “supposed” to be.

All of the children in this series have a different reason for finding a door (or for the door finding them). Some of them have miserable lives and need to escape. Others are different enough from everyone around them that they need a world where they’ll fit in. Regan Lewis’s reason starts a few years before finding her door, and it’s not because she’s different (not then), but because she makes a decision to be the same.

All of this is wrapped up in the complicated psychology and politics of friendship when you’re a seven-year-old girl. Regan rejects a friendship that might turn her into an outsider, and sticks to a difficult but safe friendship with someone who has very strict ideas about what “normal” girls are supposed to be.

Ironic, since Regan learns from her parents when she’s ten that at least some of this “normality” isn’t an option for her.

“Sweetheart, what matters most is that you understand there isn’t anything wrong with you. You’re exactly the way you’re supposed to be.”

The science of being intersex is so much more complicated than my first exposure to the concept (Jefferey Eugenides’s Middlesex, which I highly recommend). There’s a whole range in between man = xy and woman = xx, but the upshot here is that Regan was born physically female but chromosomally male. I think McGuire handles a very difficult situation well; Regan’s parents have gotten as much information as they can, and they’ve looked into all the options for treatment if it’s ever necessary (with the biggest deciding factor in “necessary” being what Regan wants). They love Regan unconditionally, they say all the right things, and they assure her that she’s perfect exactly the way she is.

You’ve probably already guessed that nothing they say helps, especially when Regan decides to trust someone else with this information.

The mysterious door marked “Be Sure” appears right when Regan needs it, when the reader is already saying “Run for your life!”. She steps through the door and into a world of forest and grassland, clean air and unicorn herds, and a boisterously cheerful centaur woman who’s utterly delighted to meet her and wouldn’t have cared about Regan’s chromosomes even if she knew what chromosomes were.

Regan’s obviously panic-stricken parents and the time it will take before she sees them again (which the author foreshadows from the moment she steps through the door) are pushed further and further back in her mind as Regan is swept away by the world of the Hooflands.

There were smaller tents, wooden constructs that looked somewhere between temporary and permanent, and there were people. Centaurs like the ones Regan knew. More delicate centaurs with the lower bodies of graceful deer and the spreading antlers to match. Satyrs and fauns and minotaurs and bipeds with human torsos but equine legs and haunches, like centaurs that had been clipped neatly in half. It was a wider variety of hooved humanity than Regan could have imagined.

Every world McGuire has created for this series has its own rules, its own geography, its own magic. I’m not sure where the Hooflands falls in the previously introduced classifications of Nonsense, Logic, Wickedness, and Virtue, but in the minor directions of Whimsy and Wild it definitely leans toward Wild (with the unicorns – who are entrancingly beautiful and so stupid they sometimes stare up into the rain until they drown – providing some Whimsy.)

We only get to see one section of the Hooflands, but it has plenty of tantalizing details like the politics of centaur relationships, or the biology of unicorns and the fact that domesticated ones are bred for longer and sharper horns. There’s the attitude of different races in the Hooflands towards each other, McGuire’s dreamlike descriptions of forests, whether the sprawling ones in Regan’s new realm or the tiny fragments bound in by subdivisions (“Even the smallest remembers what it was to cover nations, and the shadows they contain will whisper that knowledge to anyone who listens.”) Best of all it has Regan’s new centaur family, including a lonely centaur girl who becomes Regan’s best friend.

In Chicory, she had finally found a friend who liked her for who she was, not for how well she fit an arbitrary list of attributes and ideals.

Regan’s relationship with the eight centaur females of her new herd was by far my favorite part of the whole story. They’re tickled that a rare and valuable human stumbled across their herd first. They know humans appear in the Hooflands when they have a destiny to save the world, but they’re in no hurry to push Regan to find out what that actually means. They accept Regan, appreciate her, believe her unquestioningly when she says she’s in danger, and they drop everything, everything, in order to do what’s necessary to keep her safe. And not even one of them complains or makes Regan feel bad about the upheaval in their lives. It’s magical.

It’s an utterly idyllic life, and this is the part where I have, well, it’s hard to say a problem since it’s an integral part of the entire series. In the moments where Regan is the happiest and most content, I’m still sitting there waiting for all her happiness to end. The Wayward Children of this series aren’t the ones who say “it was all a dream”, or run in terror back to their own lives, happy to have survived. They’re the ones who make new friends and find a home that fits, and then one day they find themselves back in our world, and they spend the rest of their lives trying to find the door to get back.

It’s a testament to McGuire’s writing skill that she can get you right in the heart with how much this hurts, and still have you wanting to read more.

You really couldn’t pick a more resilient character than Regan, or one more resourceful and willing to make the difficult decision to protect her loved ones. She rejects the idea that she’s destined to do a damn thing (destiny, after all, being just one more thing that someone else has decided she’s “supposed” to do), and when she does try to save the world she does it not just by showing everyone that they’ve been dealing with the problem the wrong way, but that they’ve been dealing with the wrong problem. (Shout out to C.S. Lewis here, since this feels like a serious dig at Narnia.)

If she was going to save the Hooflands, she had to be this version of herself, this awkward, half-wild, uncertain girl who’d grown up on a centaur’s back, racing through woods and breathing in air that always smelled, ever so faintly, of horsehair and hay.

The beauty of theses stories are matched by the almost relentless sadness of children having to lose what they love. We’ve seen the occasional Wayward Child find their door again, so I have some hope that a future story will have Regan showing up at Eleanor West’s doorstep, and we can find out where she goes to from there (and everything that happened after her first story stopped.)