I never need an excuse to read one of Becky Chambers’s stories, with her whimsical world-building and unique brand of optimistic science-fiction. But after the first book in her Monk and Robot series won the Hugo award for Best Novella, it seems like a particularly good time to read the sequel. So let’s dive back into the adventures of the tea monk Dex and Splendid Speckled Mosscap, the robot who’s been assigned to ask every human it meets: What Do Humans Need?

Imagine having a traveling companion who’s never really traveled before, who has the wonder of a child and the enthusiasm of a tourist and a brain that can absorb literature and culture at a breakneck pace and then asks questions about everything.

What you end up with is someone like the robot Mosscap, who will slow a journey down to a crawl in order to marvel over each and every tree in an autumn forest. You’ll also have someone who will wake you up at sunrise to talk about a book it’s just finished reading, or cheerily announce “Congratulations on having sex last night” no matter who’s in earshot, or turn dinner preparations into a philosophical debate.

It would seem like an irritating situation for Sibling Dex sometimes, except that Mosscap and Dex have built a companionship that never stops being delightful. Mosscap is eager to understand everything, and is eternally pleased to answer questions from the curious citizens of Panga. The questions it asks can usually spark some thought-provoking ideas about humanity in general, and its enthusiasm for day-to-day events like owning things is infectious.

“…we can get you a satchel or something, if you want, so you don’t have things rattling around inside you.”

Mosscap stopped laughing, and looked at Dex with the utmost seriousness. “Could I really?” it said quietly. “Could I have a satchel?”

It’s in Mosscap’s nature to take nothing for granted, so it will question and discuss and otherwise pick at all the threads of every possible topic, from the makeup of a family unit, to the ethics of killing a fish for dinner, right down to the possibility of its own continued existence. The first book established that the robots of Panga don’t take pieces from other robots for repairs; there will never be a situation here like C. Robert Cargill’s Sea of Rust, where robots cannibalize each other in a desperate attempt to survive. The robots instead allow themselves to eventually fall apart, and then use the pieces to make new robots. A patch or two is fine, but the idea of 3D printing a replacement part out of an organic material is enough to start an existential dilemma.

All this philosophy could have gotten a little heavy, but Chambers mixes a lot of humor into every conversation. I loved the reactions to some of Mosscap’s questions and tangents, and the comedic beats would make me smile every time.

“You’ve lost me,” Dex said.

“Skeletal genes. Research shows there’s a correlation between them and a tendency towards insomnia.”

Dex blinked. “The hell have you been reading?”

“Everything,” Mosscap said.

Leroy took a loud, crunching bite of his apple, looking entertained.

Like most of Chambers’s other works, there isn’t a disaster to survive, or a murder to solve, or an evil plot to overcome. There isn’t an antagonist, unless it’s the villain that literally every human being has to deal with at some point: the overwhelming feeling that we’re somehow failing at our own lives. Maybe we’ve done everything we thought we were supposed to do and it’s making us miserable. Maybe we followed our passion and against all odds we made it work…and we’re still unfulfilled. The previous book ended with Mosscap reassuring Dex that just being was wondrous without some great big purpose to justify it. But both of them are still worried about what happens if the purpose they do find isn’t really achievable, or that they can achieve it and then everything has to change.

There aren’t any easy answers, but there is the beautiful world of Panga, where humans have gotten their shit together and have been spending the last few centuries making everything wonderful. Everywhere you can see the signs of the careless past and what humans have been doing to fix things. The village of Stump is named for, you guessed it, a house-sized tree stump in the middle of a now-vibrant forest with a beautiful tree-house neighborhood. There are seaside villages that exist without any technology in an Amish-like attempt to reject anything that would damage the world. And in the Riverlands, Kat’s Landing is a Maker’s dream, with an entire city built half-on and half-off the river, crafted from the repurposed wreckage of the Factory Age.

…resilience had not been the builders’ only intent. Flights of fancy could be found everywhere. There were windmills and whirligigs made of old-fashioned bicycle wheels, mosaics crafted from bottle caps and resin, sculptures decorated with splashes of forbidden materials sporting colors found nowhere in nature.

This entire novella is a dream, but less of a fanciful daydream and more of a “what if” imagining. What if humanity could learn from our mistakes and actually tried to make things better, not just for ourselves, but for each other? The story title comes from something that happens when trees are in perfect balance with each other, giving each organism the space to grow and be healthy. Imagine what would be possible if humans could actually learn to do that for each other.

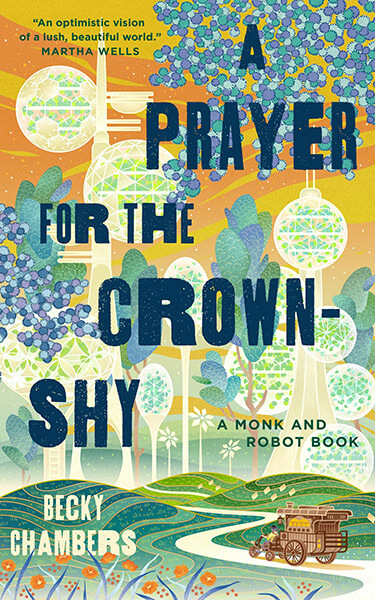

Cover art by Feifei Ruan