“I’m a troll,” he said. Then he paused, and added, more or less as an afterthought, “Fol rol de ol rol.”

Thanksgiving is over, so it’s officially time to start shopping for Christmas presents! (Unless you’re one of those highly organized people who got their Christmas shopping done before October, in which case I DON’T WANT TO HEAR ABOUT IT.)

If you’re shopping for someone on your list who’s a literary enthusiast and loves fantasy/sci-fi, then you can’t go wrong with something by Neil Gaiman. Dark Horse has been releasing a steady stream of individual Gaiman stories, each one a little jewel of a tale illustrated by a different artist (Pixelated Geek has already reviewed two of them.)

I randomly picked up a copy of one of these from last year, and I was delighted to discover it was illustrated by Colleen Doran, who’s art I’ve been on-again-off-again familiar with for about twenty-five years. The combination of Doran’s art and Gaiman’s story Troll Bridge does not disappoint.

First thing you need to know about this book is that the publisher’s description for it is crap. “As the beast sups upon a lifetime of Jack’s fear and regret, Jack must find the courage within himself to face the fiend once and for all!” Who writes these things? There’s nothing triumphant about this coming-of-age story. In fact, what happens to the main character is the exact opposite of triumph.

It’s hard to blame the publisher for that, because this story is really hard to define. It could be a simple fable (a fairly grim one), or it could be an allegory about growing up, and how we lose that way of looking at everything around us in wonder. Neil Gaiman’s description of childhood has always been balanced between an adult’s view of how the world really was, and a complete understanding of what the world was like. The sheer amount of things you hadn’t discovered yet meant there were potential adventures (and potential monsters) everywhere. It could be scary sometimes, but it also could turn a simple walk across a wooded section of an English suburb into a fairy tale.

Colleen Doran’s illustrations magnify the dreamlike feeling to the story. I first fell in love with Doran’s art in the late 1980’s when reading a friend’s copy of the first A Distant Soil graphic novel, then fell out of love with it when the series kept having to be reset multiple times (not her fault; Colleen seems to have run afoul of every underhanded publisher and data archive snafu you can imagine)(also I found some of the early WaRP Graphics issues and I really didn’t like them. Sorry Colleen), and have been slowly falling back in love again every time I stumble across something new.

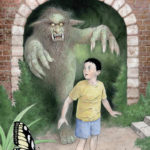

Doran’s art has evolved and matured over the years, and her artwork for this story is done in a beautiful, colored-pencil style, with sharp intricate inking that make this look like a children’s book, at least until the troll arrives and things get much darker.

“Trolls can smell the rainbows, trolls can smell the stars,” it whispered sadly. “Trolls can smell the dreams you dreamed before you were ever born. Come close to me and I’ll eat your life.”

If I had to pick a favorite section, I think it would be the part of the story when the main character, Jack, is not quite an adult but almost not a child anymore. Jack falls head-over-heels for a girl at his school, and the pictures Doran creates for Lousie are just lovely. There’s a real spark in her eyes and her grin; it adds even more life to Gaiman’s description of an innocent teenage romance that hasn’t yet gotten past the stage of holding hands and stretching out an evening as long as possible by walking each other home, back and forth, for hours. You can really see in these illustrations why Louise would be Jack’s first love.

It doesn’t stop him from trying to offer her life to the Troll in place of his.

If I have one complaint it’s that Doran draws Jack with an almost evil smile every time he tries to bargain away someone else’s life, and that just wasn’t how I pictured it when I first read this story in Gaiman’s Smoke and Mirrors collection. I always saw it as more of a desperate, grasping need to live just a little more, to put off the Troll’s desire to eat his life no matter what it cost him, and not some kind of meanness that made him enjoy throwing someone else away.

It’s a minor quibble, because whether he enjoys it or not, the end results are the same. Doran’s illustrations get darker and darker as everything from Jack’s childhood is bulldozed down and replaced with tract housing, and Jack grows older and shallower. And he doesn’t even have the luxury of blaming anyone other then himself for not having anyone in his life that he really gives a damn about.

She left a letter, not a note. Fifteen pages, neatly typed, and every word of it was true. Including the PS, which read: You really don’t love me. And you never did.

The reader is left to wonder if meeting the horrifying Troll was what ate away Jack’s connection with other human beings, or if the Troll wanted to eat his life in the first place because he could smell something broken in him, even at seven years old. The ending of the story is the definition of “bittersweet”, because like a lot of Gaiman’s stories it isn’t a happy one, but it isn’t entirely sad either, because both Jack and the Troll get exactly what they want.